(from Mickey Becket Collection)

|

Gen and Casey Miller Family Gen Olson Miller

|

One of my earliest, half vague memories is a train ride from North Dakota to

Lantry, South Dakota. Aunt Myrtle Farstad, recently married, went to Ole's

to take Frances and me to our Olson grandparent's farm, two miles north of

Lantry. I remember riding in an elevator in a hotel, and ordering

strawberries for breakfast. I have no other memories of the trip until we

got to Lantry. This was in May of 1922. Gramp Olson met us with a team and a

sled or wagon. When we got to the farm, Gram had the table set and supper

ready. Frances, only about three years old, grabbed a large piece of meat

and stuffed it into her mouth. I was mortified. There is a large gap in my

memory after that, but life must have proceeded in a normal way, for the

farm was always "home" and Gram and Gramp "our folks." They were hard

working, kind people, and made us feel we belonged.

I can still taste Gram's special chicken soup, her coconut cake, pork cake,

fatigmond (fattigmand ), ebleskiver, kernmilkers veiling, and "fried cakes". We ate WELL

.... and often! One thing I don't want to remember is her rich, buttery,

creamed potatoes. One suppertime when I was 6 or 7, I had about cleaned up

my first helping of potatoes when Gramp took a large second helping. I

yelled, "Don't eat all the potatoes!", and he passed the bowl to me. A huge

second helping went down ... and came back up about midnight. No more for

me! For awhile, every time she served them, someone would yell, "Gramp,

don't eat all the potatoes!" The joke on Frances was about "fried cakes" ...

doughnuts. When she started school, she was quite plump and a neighbor lady

teasingly said, "Frances, you look like your grandma doesn't feed you very

well." Frances almost cried and said, "No, she doesn't. She only let me eat

two fried cakes for breakfast." This of course, was on top of breakfast!

I was very protective of Frances in school, though we often disagreed at

home. One day when she got angry at me, she tore into the house and yelled

at Gram, "Where is the AX?" Gram asked what she wanted it for. Frances

answered, "To chop off her head!" Gram said, "Oh, it is by the windmill."

Frances meekly said "oh" and that was the end of that. The windmill was a

sore point for me. Frances could shinny to the top and sit on the platform

just under the fan. I got dizzy twelve inches off the ground and never made

it halfway up the windmill.

Gramp enclosed a small space between the granary and the chicken house for

our doll house. The chicken mites found their way in and covered everything.

Once we forgot to put our dolls and toys away and a heavy rain ruined

everything in the doll house. Oh well, we had about outgrown it anyway.

I couldn't wait to start school. In nice weather I walked the two miles with

neighbor kids, though Uncle Art gave me a ride in his Model T Ford when he

could. He and Myrtle lived 1/2 mile from our place and if I got there on

time, I could ride with him. He ran the Lantry Lumberyard. He always had a

Hershey bar or some other treat for me. He would let me sit on his lap and

steer his car. This went to my head and I told the neighbor girl I could

drive. She needed proof, so I told Uncle Art. With her along, he let me

steer all by myself and I headed straight for the ditch. He rescued us, but

I had made my point... I could drive (though not well!).

The next summer there was a large Indian Fair in town. Everyone for miles

around attended. When we got there, Uncle Art took Frances and me to

Woodward's store and bought us chocolate ice cream cones. What a fabulous

treat. We smeared our faces, so he bought a new handkerchief to wipe off the

ice cream. As he was returning us to Gram's care, Frances let go of his hand

and rushed up to a line of Indian ponies tied to the hitching rail in front

of Miller's store. One half-broken pinto let fly a back hoof and caught

Frances just under the chin. It knocked her cold and really caused a stir.

A number of women were visiting at the living quarters of the store and they

and Gram, came running. Each had a different version of what should be done.

There was no doctor, but after cold, wet cloths on her head, and whatever

else they used had brought her back around, she didn't seem to suffer any

drastic after effects. I was worried sick and wondered why she would ever

try anything so reckless.

I had a very special friend, Sheila McDaniel. Her parents lived about a mile

from our place and we were the only two kids in the first and second grades.

Her brother, Bobby Gene, became old enough to drive the old horse that

pulled the buggy, and l rode to school with them. Bobby Gene wasn't above

snatching cookies from my lunch and I always bawled loudly enough for the

teacher's sympathy.... and sometimes one of her cookies.

Three or four years later, Myrtle and Art moved from North Dakota to South

Dakota. Lois went to visit school with us. I was really protective of her.

She was so little and I was so fond of her. When the teacher scolded her for

talking, I decided to dislike the teacher for life, although she had been my

idol until then.

Looking back, our school was quite progressive for its day. We had

advantages the country schools didn't have and yet it would really seem

primitive to today's students. There were two rooms, four grades in each,

and a teacher for each room. Upstairs were two more large rooms, one where

the teacher or teachers lived, and one for a winter playroom, or a place for

school parties and YCL meetings. My first year, a married couple taught.

Mrs. Wynn had 1-4 grades and Mr. Wynn had 5-8. My second year, Grace Eustice

taught 1-4, and Margaret Aidelotte taught 5-8. Margaret was a local

girl who helped her dad in the fields in the summer. The summer before, she

was cleaning the sickle on a mowing machine when the horses jumped and one

foot was cut off. We small children were glad she wasn't our teacher as she

was so cross. I suppose she had pain and it must have been hard to start

school so soon after the accident. Before the year was up; she had an

artificial foot, but it hurt her to wear it, so she didn't.

When I was to start 3rd grade, Mr. and Mrs. Art Koch were hired. She taught

1-4 and he had 5-8. Since I was the only 3rd grader, she let me take both

3rd and 4th grades that year. The next year I went into Mr. Koch's "upper

room" in 5th grade. We called 1-4 the "lower room", and 5-8 the "upper

room". He was my teacher for the next four years. The year I graduated from

8th grade, he ran for County Superintendent and won the position. When we

moved to the Black Hills, I was disappointed to learn he owned and operated

a bar in Rapid City.

My first year of high school, 1931-32, I worked for my room and board at

Alice Vance's. Times were rough (depression!) and we didn't have many

clothes. My aunt, Margaret, always liked fancy high-heeled shoes. When they

got too shabby for her, I took them. One Friday night when I was too

homesick to stay away another minute, I decided to walk home. Lantry was

15-17 miles from Dupree, and our home was two more miles north of Lantry. I

started out in a pair of Margaret's cast off spike heels, and what a walk!

It got dark and I was scared. However, I was halfway and there was no use to

turn back. The highway was gravel and OH! my aching feet! I barely knew Bill

and Liz Ochsner, who were newlyweds. She had graduated the year before and

they had been married that summer. They drove up to me in their old coupe..

or roadster.. and I couldn't see much room in it, so I turned down a ride.

Mostly I was painfully shy and didn't know what else to do. I thanked them

and they drove away. I made it though, and was I glad to get home. I

never tried walking it again. There was a train that ran between the two

towns, and once or twice I rode it to or from school.

As I got ready for school at the end of September of my freshman year, a

post office clerk brought me a registered letter. Everyone stared as I read

it. It was from Aunt Myrt. Uncle Art, a night watchman, had been shot by

burglar. The bullet entered a lung and he was in critical condition. Myrt

thought I could break the news to Gram and Gramp. I caught the train to

Lantry and told Mr. Woodward. He drove me to the farm. We learned Gram was

with Margaret at her school near Timber Lake, so he volunteered to go get

her.

I walked to Lantry to catch the evening train back to school, and left

Gramp and Frances "batching" at home.

The winter of 1932, my dad moved his new family, a wife and two small

children, to Minnesota. He stopped to tell me goodbye and gave me $10.00.

WEALTH! I bought Christmas presents for the whole family from the Sears

catalog and Alice Vance told everyone I could stretch money farther than

anyone she had ever seen.

My second year of high school 1932-33, I worked for room and board at Art

and Erma Hurst's. They were terrific! Their only child, Raydon, was 1-2

years old. I would babysit him after school if Erma helped at the drugstore.

I also would help cook and clean, although it was easier work than any place

I had ever stayed. Erma's sister's husband lost his job though, and their

family moved in just before school was out.

In 1933 I moved back to Alice Vance's. I was now a Junior and it was

suggested we each try to earn our own class ring for the next year. They

cost $6 or $7, and not many people could afford them. Just as school ended,

Erma Hurst called me. Her sister's family had found a house. Raydon had

measles and they were quarantined alone, as Art couldn't go into the house

and then back to the drugstore. Would I come and stay a few days and keep

her company? Would I!

While there, Fred Barthold came and asked if I would be his wife's hired

girl for the summer. They lived along the Cheyenne River, way south of

Faith. I soon found out what WORK meant! Mrs. Barthold was allotted $30.00 a

month for a hired girl by the corporation for which they worked. I got $3.00

a week, and she kept the rest. She was the most disagreeable human being I

had ever met, but when she asked me to go to Rapid City for the school year,

I agreed. There would be no pay, as I would be working for room and board.

Their two boys were in high school and she planned to take an apartment for

the winter The only other alternative I had was to work for the judge's wife

in Dupree, and the lesser of two evils was to go to Rapid City. There were

few clothes and no money, but plenty of homesickness. After the holidays,

Mrs. Barthold and I parted company and I worked at another home, with nice

people, until graduation.

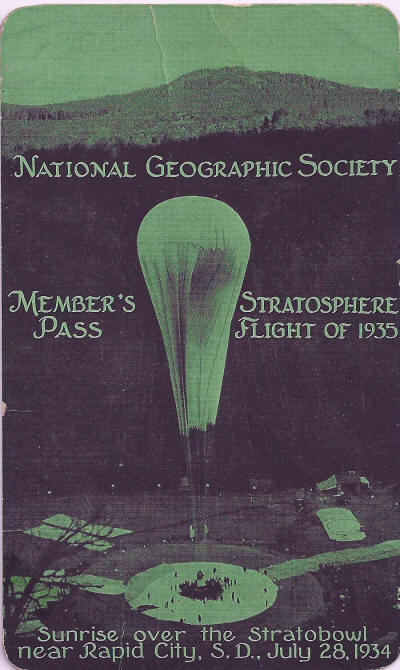

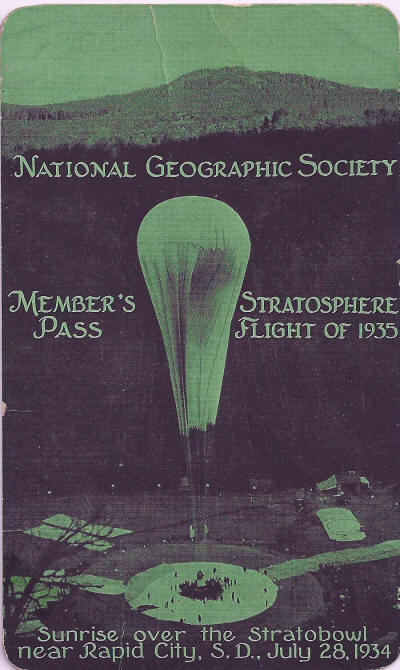

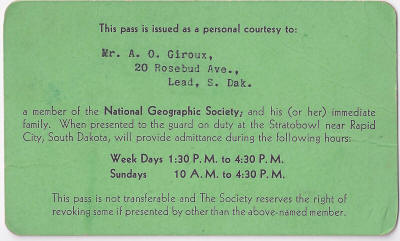

Highlights of that year were being elected to "Quill and Scroll", an

honorary journalism society, working on the school paper, and being chosen

to interview the men who would make the stratosphere balloon flight that

summer. My journalism teacher got me the job covering the flight, but I was

unable to do it as relatives came for graduation and insisted I go home to

Lantry.

(from Mickey Becket Collection)

(click both pictures to enlarge)

(from Mickey Becket Collection)

Coming from tiny Dupree to a class of over 200 seniors in Rapid City

was a challenge. I really enjoyed school though and managed to graduate cum

laude.

I started to itch on the way back to Lantry, and awoke with a full case of

chicken pox. Later we learned I had acquired it from the rented cap and gown

at graduation, as many others also got them.

After I graduated from high school in May 1935, I went home to Lantry. A

lady I had known quite awhile was starting a cafe in Dupree, her first

venture. I worked there all summer for $3 a week when she had it, and less

if she didn't make enough to pay the help. One day she sent her teenage son

and me to her home to get something from the basement. When we got there, I

smelled a funny odor and asked the boy if he also smelled it. He said,

"Yah.. see all those cherries Ma canned? A friend and I loosened the lids on

some so they would ferment and make wine." I never followed through on that,

and don't know if he got caught. It was my job at the cafe to mop the dining

room floor in the afternoons when there were no customers, One day as I was

mopping, the owner called to tell me a band of gypsies had come to town. I

was to hook the screen door and NOT let them in. I did. One gypsy lady got

very angry at me and kept yelling through the screen door. She said she was

going to put a curse on me. Just then I saw Casey sauntering down the

street. I got him to come and stay until the gypsies had left. As soon as

they had pestered all the merchants, they got into their battered old cars

and left town. In late fall the cafe owner could see her business was a

failure and I went home to Lantry.

A surveying crew came to Dupree and made extra work at the established cafe,

so I was hired to work until they left. I worked until late November when we

extras were laid off. I hated to just sit around, eating off Gram and Gramp,

because the depression had left them in pretty bad shape. Margaret asked me

to come live with her, in a school teacherage, about 5 miles south of

Lantry. She was going to get a divorce and was afraid of what her husband

might try. The teacherage was a tiny room tacked onto the end of the

schoolhouse. I had to be very quiet as I did the dab of housework and

cooking. When Margaret was ill, I substituted as teacher. I pretended to

know what I was doing and the kids didn't seem to notice I wasn't a regular

teacher. We were bored most of the time, for we had no car. We listened to

the radio, read, and embroidered tons of things.

In February we had an extremely cold spell with a lot of snow. We hadn't

been able to get to Gram's for the weekend and were getting low on food.

Clara and Ernie lived about 1 1/2 miles from the school, so on Saturday

morning we decided to put on all the clothes we could find and walk to their

place; Clara was a super cook and we knew we would be well fed. We misjudged

both the cold and the amount of clothing we had on, and when we got to their

house, Margaret nearly collapsed. I found both of my upper legs were frost

bitten and turning white. Ernie got a pan of snow and rubbed the white

flesh, and then had me soak in warm water. It was quite a painful session of

home remedy. The injured flesh later turned a queer, dark color, but

eventually became okay. We had no way to get to a doctor and I guess we

never even though of that.

In March of 1936, Casey and I were married, but Margaret asked me to stay

with her until school was out when she would move back with her folks. Casey

had bought a place just west of his parents' home and we would go there

weekends to try to clean and fix up the old house. One week, trying to

surprise me, Casey got a small can of green paint and started to paint the

kitchen ceiling. One third of the way across he realized he didn't have

enough paint.; He thinned it well, but after painting another one third of

the ceiling, he had to thin it further to have enough to finish. We had a

"three shades of green" ceiling. We had no stove so Grandma Miller would

pack us egg sandwich lunches. I would return to the schoolhouse on Sunday

afternoons.

Just before we were ready to move into our place, I was told there would be

a charivari (called a chivaree around there). It was the custom to chivaree

newlyweds and things sometimes got pretty rough. After one wedding the men

grabbed the bride, put her in a wheelbarrow and ran up and down Main Street

with her until everyone was exhausted. We were afraid they would ruin her

beautiful wedding dress. It wasn't unusual to grab the couple and put them

in a hay wagon to be driven all over town. One couple wouldn't let the

partiers in, knowing they probably had plans such as this, so they plugged

their chimney until it smoked them out. I was nervous until I found out it

would be at Casey's folk's place. Grandma made several cakes and homemade

ice cream. The few men who had to have booze kept it outside. When the party

ended, it had begun to rain. We headed for our place and got stuck in a

creek bed. Casey had to walk back to get Fred to pull the car out of the

mud. Fred teased us for a long time about having to get Old Mary, his horse,

and rescue us on our honeymoon.

As soon as school was out we moved all our worldly possessions to our

tarpaper house and set up housekeeping. Clara had given us a wedding shower,

and we received a number of enamel pots and pans, a few linens and dishes,

and lots of good wishes. We paid Gram Olson $40 for a nice cookstove. She

had bought it from Aunt Myrtle when they moved to Minnesota. Gram gave me

the brass bed and dresser that had been in my room at home, and a trunk for

storage. Casey also had a trunk, and there was an old kitchen cabinet which

had been left in the tarpaper house. (Years later brass beds and dressers

like mine were considered antiques. We had thrown the bed out and never knew

what happened to it. I still have the little dresser. The cookstove served

us well for many years. In 1978 we sold it for $200, as an antique.)

Our house wasn't much! It had two rooms, with a slant roofed kitchen tacked

onto one end. The kitchen roof leaked like a sieve every time it rained. We

would get every wedding present pot and pan, as well as anything else we

could find, and set them under the drips. We had a small wooden table and

two wooden chairs. One of these I had found out in the yard, scrubbed clean,

repaired, and put a heavy coat of varnish on it. I left to do other tasks

and came back just as Casey got undressed to take a bath. I discovered him

sitting in the fresh varnish with his bare hide.

The old cabinet, my only kitchen cupboard, seemed to always have mice in it.

I got fed up, turned it upside down, and patched every hole and crack. That

helped! The cookstove was my pride and joy and the oven suited me perfectly.

One day Casey brought in a can of tar to melt. I begged him not to set it on

my good stove, but he did. It caught fire, cracked the white porcelain

backsplash in several places, and ruined the looks of the stove forever.

Our living room contained a "sanitary cot" donated by Grandma Miller. I

never knew why it was called that, but I sure knew it could never be made

comfortable. It was our guest bed as well as the couch. We had two old

rocking chairs, one given us by Gram Olson. I don't remember where the other

came from. Casey bought a large table with four matching chairs and a

matching buffet; from Verna and Art. That made our room a combination

living/dining room. In winter we set up a small heating stove. That first

summer the crickets and grasshoppers were so bad that they ate the starched

curtains on the windows.

Our bedroom had the brass bed and dresser, plus a wide shelf in one corner

with a curtain hung in front for a clothes closet. No one needed many

closets for we had few clothes.

Our water came from the well, in buckets; and hot water came from the

reservoir on the end of the cookstove. On wash day, water was heated in wash

boilers, and clothes were washed in washtubs with the help of a scrub board

(which took off more knuckles than dirt!). In winter, the clothes were hung

outdoors to freeze, then brought in to be hung on rope lines or whatever

could be found to hold them while they finished drying. We dodged long

Johns, shirts and dresses until the heat from the stoves got them dry.

We had an old dog named Soup, which had belonged to Cully. At first we

couldn't afford a car. We would drive a team to the neighbors and ride with

them to town for groceries, or Grandpa Miller and some of the boys would

stop by and take us along to town. After a couple of months, Casey bought an

old Model A Ford truck from Cully. It had no shifting lever and the left

door latch was gone. Casey would hold the door shut with his left hand,

drive with his right hand, and I would shift gears with a long screwdriver.

Midsummer, we were awakened one night by a neighbor who told us Art and

Verna's house was burning. They lived about five miles south of us. They

lost everything but a few clothes and one mattress. We invited them to stay

with us so they brought their mattress, and Dawn and Mary. We were glad to

have them and thoroughly enjoyed the two little girls. Art's dad came to fix

another building for them to live in, and he also stayed with us. Art's dad

got the one bed, Art and Verna slept on their mattress on the floor but I

don't remember where Casey and I slept. It wasn't long until they had a

house.

Casey and I decided to go to the west coast. Crops were so poor from the

drought and grasshoppers; and there was no work in the Dupree area. We had

heard so much about the west, and decided to look it over... maybe even

settle out there. If we didn't like it, we could just say we had taken a

belated honeymoon, and come home as soon as we pleased. Art agreed to milk

the cows while we were gone. There wasn't much else to worry about. Casey

had a lot of horses and sold enough of them to buy a Model A Sedan for about

$250, and have about $500 left over. (Neither of us can remember what

happened to the old truck. I am sure Casey got something from someone for

it!)

Since we might not be coming back, we had to take our best things with us.

Casey built a sturdy wooden platform on the back end of the car, and we

lashed our trunks onto it. We packed our clothes, favorite linens, and a

supply of bedding, for we might have to sleep in the car part of the time.

When all was ready we headed north through Lemmon, S.D., and across to Miles

City, Montana, We hoped to find my Aunt Marie, whom I hadn't seen since I

was three (and couldn't remember that visit). She had kept in touch

throughout the years by letter, and we knew she owned land at Melstone,

Montana. We drove north from Custer, Montana, just west of Miles City, and

headed up a mountain for Melstone. What a bleak, forsaken area that was! On

the whole drive, we saw one tumbledown shack, a very few sheep and lots of

sagebrush. We arrived after dark and found people who knew Marie. They told

us she was staying in Forsythe and teaching at Rosebud. There were no

cabins, in fact there was NOTHING in Melstone, so we slept in the car that

night. The next day we drove to Yellowstone Park. There was a lot of

road construction, and on a detour we picked up a bridge spike in a brand

new tire. That hurt! We couldn't believe all the snow on the mountains, for

it was August. We saw Old Faithful Geyser, the Paint Pots, and could only

look longingly at the fancy hotel and eating places. We went out of the park

on the other side through the northwest gate, and drove about halfway to

Bozeman. Again, we slept in the car. When we started out the next morning

the car began to overheat. Upon investigation we found the radiator had

frozen in the night. We weren't used to judging temperatures in high

altitude! No damage was done and we continued on our way. I bought a warm

jacket in Bozeman and then we headed for Kellogg, Idaho, where we knew some

former Dupree people. As we drove through the mining country, we knew we

didn't want to settle there. We enjoyed the drive however, as the scenery

was beautiful and we saw some bears.

The only place I didn't enjoy was Butte, Montana. We had stopped there to

eat and saw the street was filled with picketing miners, protesting low

wages. I had heard about pickets but had never seen any, and we ate rather

quickly and got out of town. We found a cabin court down the road and spent

the night there. We rented several cabins, coming and going, for 25 cents,

50 cents and 75 cents a night. They had hot plates to cook and sure beat

sleeping in the car.

The following day we drove into Kellogg, found our friends and visited

awhile. When they insisted we spend the night, we rolled out our bedding

onto their porch and slept in style.

We decided to go on to Washington State where we had more friends, and they

might know of available work. They welcomed us with open arms and said we

should stay there. Casey could get work in the wheat harvest fields. These

people worked for a family who owned huge orchards, and had just

finished-picking the cherry crop. There was fruit everywhere we looked, and

fresh vegetable stands all along the roads. As we traveled, we would buy

crates of fresh tomatoes for 25 cents, and eat our fill. We feasted on melon

and other fruit. In the evenings we would buy bread and hamburger and cook

our suppers in a cabin. In Washington everything looked promising!

Casey applied for work and was hired to pitch bundles of heavy, irrigated

wheat into hayracks. The farm was fenced with a padlocked gate, and the men

were let in as they arrived for work. They had to carry a sack lunch from

home. Casey loaded about 20 loads of the heavy bundles a day, coming home

exhausted, and for all the work was paid $3.50 a day. On the third day he

was sick of the whole situation. We left Washington without even collecting

the wages he had earned.

We headed for Portland, Oregon, where Casey's Uncle Lute and Aunt Anna

lived. He had been there the year before for a brief visit, and liked the

area. We arrived at the edge of town at dark, in a pouring rain, and didn't

know our way around. We had no more clean underwear, so rented a cabin, ate

at a hamburger place, and went back to the cabin to do some hand washing. We

found some string and hung the wet things here, there and everywhere, hoping

they would be dry by morning. The humidity was high, and being used to the

dry, hot weather at home, we weren't sure the clothes would ever dry. As I

finished, Casey sat down on the edge of the bed to get ready for a good

night's sleep. Horrors! The bed collapsed and we couldn't get it put back

together. Casey got the owner, who made snide remarks while looking at the

wet laundry strung all over, but he fixed the bed. He finally told us he'd

had some "roughnecks" stay there the night before, and wasn't surprised the

bed had fallen apart.

I was really nervous about meeting relatives, and would have liked to stay

in the cabin, but the next day we drove to Uncle Lute's place. There Casey

decided it would be a good joke to sit in the car and have me go tell Lute I

was a Miller from South Dakota. I did. Lute looked at me and said, "No,

you're not a Miller." Casey rescued the flat joke and we got royal

treatment. Here too, fruit was falling off trees, because prices were so low

the orchard owners couldn't afford to pay people to pick it. They were

turning cattle and pigs into orchards to clean up the fallen fruit. Coming

from an area with no fruit, it drove me crazy! Anna insisted I do some

canning to take home with us. I wanted to rent a cabin and can things, but I

lost the argument. We headed into Portland to a big Montgomery Ward store to

get supplies. On the way, other motorists were waving at us, and we thought

it was a mighty friendly town. When they started to point as well as wave,

we discovered we were driving the wrong way on a one-way street. Casey's

famous "bootlegger turn" got us headed right. I bought a large blue enamel

canner which I used until 1980, when it finally sprung a leak, 100 fruit

jars and some jelly jars and lids, plus sugar and wax for jelly. We got a

large tin preserve kettle, which once back home couldn't take our alkali

water and leaked in a year or two. I had helped Gram can, so knew how; but I

followed Anna's instructions as she hovered right over me until I had 100

quarts of fruit and several glasses of jelly sealed and packed to go home

with us. We put the filled jars back in the boxes they'd come in, so they

would survive the long trip home. (We had lots of company that winter when

word got out our cellar was full of plums, peaches, apples and a few pears.)

Lute and Anna said they had tried hops picking when they first lived there.

It was time to pick them and we decided we would try to earn some money.

Anna said I would have to wear slacks to work in the field, so we bought a

pair for 99 cents. We found a hops farm where whole families were picking;

some had children of all ages helping, so we decided we surely could do it

also. We got hired and were given a sack large enough to hold a bed

mattress. Hops are green, leafy pods that are used to make beer or ale. The

pods are overlapping layers of leaves, sticky and aromatic. The heads of the

hops were about 2 to 2 1/2 inches long, and 3/4 to 1 inch across. As we

started to pick, our hands turned green, then black, and our fingers stuck

together. The sun was hot and our backs ached, but we worked as fast as we

could to fill that sack. FINALLY it was full and we took it to the weigher,

who would pay us according to the weight we had picked. $1.63!! With 99

cents for slacks and the gas to drive there, we weren't exactly getting

rich. We left and never looked back!

They took us to the State Fair in Salem and we had a grand time. Anna packed

a huge picnic lunch. We were joined by their bachelor son, their married

son, his wife, and their little boy who wasn't old enough to walk. We took

turns pushing the stroller and saw all the sights.

One day Casey and I decided we had to see the ocean. He wanted to see a

former friend from Dupree who lived in the area. We found their place and

enjoyed a short visit. They worked for relatives who raised mint, and had a

distillery. Did it ever smell nice around there!

We decided it was time to head back home. The west wasn't the dream place we

had been led to believe, unless you were already well established. Ranch

life looked pretty good to us. We had just one thing left that we wanted to

do, and that was to find Aunt Marie. As we were getting ready to leave, Anna

insisted she and I have a little shopping spree. I don't know what it was

that she wanted for herself, but she was very firm that I get a new dress

and hat. She picked out a dark green knit boucle, two-piece dress. I bought

it and a green hat to match. Women's hats looked just about like men's hats

that year, except they came in bright colors. That done, we headed home.

Since we'd had such a nice vacation, we decided to take turns driving and

sleeping, to save some time on the return trip. The trip west was the first

time I had ever driven mountain roads, but I had done okay on the way out

and didn't worry about it a bit. The roads were wonderful... nothing like

the gumbo or gravel roads at home. Casey drove until we were high in the

mountains, just about dark. We switched places and he promptly fell asleep.

All went well until I happened to glance into the rear view mirror and saw

what looked like a man riding on our trunk. Had a hobo hitched a ride? I

figured if I speeded up, then hit the brakes, I would dislodge him, or at

least shake him up. I tried it, but he only slid to the other side of the

car. Try again .... but no luck getting him off. I thought I had better

awaken Casey and see what he thought we should do.. He was pretty groggy,

but he leaned across the boxes of canned fruit trying to see the back of the

car. Suddenly he said, "It's your new hat!" It had slid out of the sack and

skittered across the shelf under the back window. He went back to sleep and

I drove on.

I think we were more tired than we realized, for we don't remember too many

details about the drive to Forsythe, where we found Aunt Marie. She was

staying with old friends who insisted we come in and stay awhile. We spent

that afternoon and night, getting acquainted with Aunt Marie. It was a

Sunday, and she took us to see her school at Rosebud. The next morning we

followed her as she headed for school, and as we came to the place where we

turned to take a different road, she got out of her car and came back to

ours. She said, "I think you have a very nice husband, even if he is an

Indian!"

It seemed that once we were headed home, we couldn't wait to get there. We

didn't waste much time along the way. The last day we decided if we took

turns driving and didn't stop to sleep, we could get home late that night. I

had taken my turn at the wheel and was dead tired. I curled up in the car

seat; put my head in Casey's lap and conked out. The next thing I knew,

something very hard was trying to smash my forehead. I struggled up to see

Casey yank the wheel around and fly across an irrigation ditch. He had

fallen asleep, jumped the ditch, and when he woke up he jumped back across

and onto the road. The steering wheel had made a nice red welt on my temple

and we were both wide awake after the scare. The biggest mystery is how the

jars of canned fruit survived without even one cracked jar. We sure couldn't

have duplicated it with our eyes open and still don't see what kept the car

from rolling over. We did get home that night, with over half of our money

left. It was a wonderful trip but it seemed awfully good to get home.

We got ready for the long winter, buying sugar, flour, and other staples,

and thought we were all set until spring. In late November I got sick ....

then sicker. Casey bundled me into the car and drove to Lantry to see what

Gram and Gramp thought. Margaret was still living with them and recognized

appendicitis, for she had lost her appendix a few years before. She got

ready to go with us and we drove the 100 miles to the Pierre Hospital,

arriving there between 10 and 11 pm. My appendix was out by midnight. I

spent Thanksgiving day enjoying the first solid food I'd had in over a week.

I never knew pumpkin pie could be cut into such TINY wedges and still be

called a piece of pie! I had worn my new green dress, and had pinned my

treasured Quill and Scroll pin to the collar. When it was time to go home,

the pin was gone and I never saw it again. That hurt about as much as the

surgery! Casey sold a horse for $150 to pay the hospital bill.

We had a few modern conveniences in our tarpaper house by now. Casey

bought a secondhand gas motored washing machine. It worked about every third

or fourth washday. We had a good battery operated radio. The main power was

a regular car battery, and it took two big dry cell batteries and two small

dry cell "C" batteries, This all sat under the little table that held the

radio. The car battery had to be recharged every week or ten days. When the

roads were bad and we couldn't get it to town, we had to ration our

listening. It was saved then for news and weather reports. When we had

plenty of battery "juice", we listened to Fibber McGee and Molly, Amos and

Andy, and on Saturday nights, The Grand Ole Opry. There were a lot of good

bends - each person had his favorite. The neighbor women listened to Ma

Perkins, one of the first soap operas, but I couldn't sit still long enough

for their drawn out situations. I listened to the Neighbor Lady, from the

Yankton station, because she read recipes over the air.

It was a hot and dry summer. We had something new to think about as there

was a baby on the way and we wanted to do something about that leaky

kitchen, and needed to find a corner for a baby's things. Gram and Gramp

came to spend a few days while he helped Casey tear down the kitchen. They

used the lumber to build a small bedroom off the existing bedroom. By small,

I mean just enough room for a double bed, the little dresser, a

shelf-curtain closet, and not another inch to spare. We rearranged the rest

of the house and took the living room for a kitchen. The former bedroom

became the living room with the heating stove set up in it. The weather was

nice when Marlene was born in November. However, the day before I was to go

home, it began to snow, with a hard blizzard forecast. Dr. Cramer knew that

Grandpa Miller was at a county commissioner meeting, so he called him and

asked him to take me home. When we got home the new baby crib still hadn't

arrived. Panic! We had no experience with new babies and didn't know where

to put her for the night. (Since then, we have slept babies in baskets,

boxes, and even dresser drawers stuffed with pillows!) The train came in

late at night, so Casey and a brother went to town and discovered the crib

had come.

We had to warm it up and assemble it before we could use it. I suppose I

would have sat up all night, holding her, if the crib hadn't come! She had

colic for several weeks and we soon learned it took more that a new bed to

make a baby sleep well.

The windows in the tarpaper house were long and narrow, coming nearly to the

floor. When Marlene could sit up, one morning I left her in the living room

in front of a window, and I went to the kitchen to do some work. A huge

bullsnake was just outside the window and every time Marlene patted the

glass, it would hiss and stick out its tongue. I normally would run fast and

far at the sight of a snake, but for this one I grabbed a hoe and cut it

into 3 or 4 pieces.

We had to have an icebox to keep the baby's milk sweet, and to save so many

trips to the root cellar. Root cellars were cool, deep caves, dug by hand,

with thick timbers on the roof and dirt piled on top for insulation. Shelves

were built along the walls for the canned goods, milk and butter that were

stored there. We had only a tiny dirt cellar under the house and it was

caving in, so we used the root cellar year round, much as basements are used

today. The steps into it were just dug out of earth and with use became

worn. It was easy to slip and slide to the bottom where there were usually a

few mice, lizards, or a snake or two. The cans of cream which we hauled to

town to be shipped to creameries, were stored on the floor of the root

cellar where it was coolest.

Our ice was kept in a much larger cave affair, also roofed. As soon as the

dams froze to a depth of 18 inches to 2 feet, the men gathered to "put up

ice". Long ice saws, ice tongs, ropes, and a team and sled were assembled.

The women usually came with their husbands for the day, and it was rather

like a holiday. The women would cook a big meal and the men would work hard

sawing a lot of big, oblong cakes of ice, pulling them out of the water and

loading them onto the sled. When they had it loaded, they would drive to the

ice house and make a layer of ice cakes, then a layer of straw, keeping this

up until the ice house was full. In cities, the ice was packed in sawdust,

but we had none available. The top layer of straw was a thick one. No matter

how much ice we stored, or how well the straw insulated it, by the hottest

part of July it would be all gone. There was simply no way to keep enough

for a whole summer. We had lots of homemade ice cream. When I needed ice for

the icebox, Casey would take the axe to the ice house, chop off a good sized

chunk, grab it with ice tongs and heave it into the top section of the

icebox. A pan was kept underneath the icebox to catch the water as the ice

melted. It was easy to forget to empty the pan when you were busy, and we

would see a little river of water start across the kitchen floor. Our icebox

was secondhand, but nice white enamel. We would put jar lids of kerosene

under each icebox leg to keep the ants out of the food. Our house seemed to

have been built on an ant hill and we had ants to battle all summer.

When Marlene was about 1 1/2 years old, we came into the house one day to

find her sitting on the floor in front of the icebox, carefully breaking

eggs onto the floor. When she saw us, she looked, smiled and said, "Cake!"

How could anyone scold such an intelligent child!

The living room floor was covered with several layers of rubberoid, the top

layer painted a dark maroon. We couldn't afford linoleum, so I kept that

floor shiny with homemade floor wax which Gram taught me to make. We would

put a bar of paraffin in an old pan and melt it on the back part of the

cookstove. When it was melted, we added gasoline and turpentine. Its a

wonder we didn't blow the house sky high! The wax stayed semisoft and was

applied with a cloth. After it dried awhile, it had to be polished. On hands

and knees, we would take old scraps of woolen cloth, or socks, and put a

brick inside. This was pushed back and forth, over and over, until the floor

shone. We tried to short cut the process by putting old woolen socks on over

our shoes, and "skating" back and forth, but it always had to be finished on

hands and knees.

When I was ready to bring Marlene home from the hospital, Casey decided he

had better sweep the floors since I had been gone ten days. He stood in the

center of the room and made circular swipes all around himself. When I

looked at the maroon floor it looked as though someone had painted a

huge grey daisy on it. His swipes had only rearranged the dust, not removed

it.

Marlene had two accidents in the tarpaper house. When she was big enough to

start climbing, she pulled a drawer part way out on the little dresser, to

stand on. She wanted to reach the dresser top and get "mama's 'fume", my

perfume. Her stiff soled shoes slipped off the edge of the drawer and her

nose hit the edge as she fell. Her nose was broken, but the doctor said to

just massage it after the swelling went down.

Her second accident happened when she was about three. I had been sick and

he had a young girl from town who came to help for a week. Marlene was

rocking in a little rocker, very violently. The girl told her she had better

slow down. Marlene said, "You can't catch me, Tiny Jean!", just as the

rocker went over backwards and her head hit a piece of sharp metal on the

cookstove. It bled like crazy, but healed in a short time.

Aunt Marie visited us in the tarpaper house in the summer of 1938 and again

in the summer of 1940. The men were building a large dam at our place and

Marlene picked up some choice cuss words. Every time she used one, Aunt

Marie would throw a dipper of water in her face and I would have to wipe the

floor dry.

That November, Marlene invited the grandparents. aunts, uncles and cousins

to her birthday party. I didn't know anything about it, but fortunately

Verna double-checked with me. We had a party, but Marlene had caught a cold

and felt miserable. While the cousins played happily, she spent the evening

with her head in my lap, even ignoring the gifts people had brought her.

Some former residents had moved to Idaho and wanted to sell all the

buildings on the place they had left. In October 1940, Casey bought the

house, chicken house, granary and garage. He hired a man from Eagle Butte to

move the house to our place. This was our Yellow House. Fred moved the

smaller buildings later. The house was set on a foundation, but had no

basement. It seemed large after the crowded tarpaper house. We had a nice

living room, a smallish bedroom with a closet built under the stairway, a

huge kitchen, and a walk-in pantry. The second story was one large area,

with no partitions, and was used as an extra bedroom or playroom in cold

weather. Casey built an entry to hold the washing machine and cream

separator. We had to go a little slower on cleaning, painting and moving as

another baby was on the way. But, we were determined to be settled in the

new house before the baby arrived. So many windows had been broken while the

house stood vacant, that Casey had a big job taking a few at a time to town

for new glass. I did a bit of painting, a LOT of scrubbing, and we got his

brothers to help us move and set up the cookstove and heating stove. We had

2 or 3 broken windows left to replace, but moved in and slept in our new

home for the first night.

We awoke the next day to a howling blizzard. It was November 11, 1940,

Armistice Day. We hurried to tack blankets and quilts over the broken

windows and I began to wonder what the roads would be like in case the baby

got in a hurry. The storm raged for 2 or 3 days, but we were warm and happy.

Casey was working in town and since I was home with no car, he hired a

neighbor girl to stay with me to help with the housework and Marlene. I

wasn't used to having help but the hired girl spent most of her time in the

pantry. Once, when a batch of cupcakes disappeared really fast, I found the

little paper cups stacked neatly in the corner of the outhouse. She even

snacked out there! She wasn't fussy enough in washing dishes to suit me, but

she polished Marlene's little potty every day until it shone like a jewel.

The doctor had given me some pills for leg cramps. When the hired girl

already had my goat one day, she asked what the pills were for. I told her

they were my reducing pills. When she went home for the weekend, the pills

disappeared never to be found. When I asked her if she'd seen them, her face

turned red but she didn't answer. She said she had gained 20 pounds while

working for us. What a relief when the doctor told me the baby would be

early. I let the hired girl go, and baby Ann arrived on December 4, 1940.

Verna and Art had lived in town for a few years. Verna kept Marlene while I

was in the hospital. We bought a tiny crib, which sat near the heating stove

in the living room. The winter passed quickly. As soon as spring arrived,

Casey planted the usual wheat, oats and other crops. He plowed a big garden

and I did more painting and cleaning. We moved the kitchen wall, tore out

the big old pantry and had an extra room. We used it for a dining room for

awhile, then changed it to a bedroom as the girls got older. I kept my

sewing machine in there and did lots of sewing. We bought a cabinet sink and

Casey plumbed it to drain outside, but we still had no running water and had

to carry it in pails from the well.

Cully wanted the wall sink Myrtle had given me and offered to trade an old

sow who would soon have piglets. We traded and I had to take care of the pig

who had 5 piglets eventually. I felt I owed Myrtle something for giving me

the sink. When the pigs were big enough to sell, they brought $6 each. I

sent Myrtle $6. Casey said I owed him for the feed and that Marlene and Ann

should each have one pig to buy War Stamps. I spent $5.98 for a new

winter coat for myself. I think we butchered the old sow but don't remember

her fate for sure. I disliked pigs, chickens, cows and horses, and often

wondered what I was doing on a ranch!

One winter I sewed new flannel pajamas for the entire family. The first time

they were washed, I hung them on the outdoor clothesline from papa-long to

baby-short. When I looked out the window later, the pigs had chewed the legs

off the long and medium sizes and all the pj's hung even with the baby pair.

In spite of ornery critters, these were happy years. We were far from rich

but times were better than before and we lived well. We had even bought a

bedroom set that matched! The sanitary cot disappeared and a daybed took its

place. We had a lot of company and enjoyed friends and family. Then, as we

listened to the radio one Sunday after church, the shocking news of Pearl

Harbor was broadcast. We had been well aware of the war in Europe, but now

it had hit home. With the war years came shortages and rationing.

It has become popular 43 years later to remember what you were doing when

Pearl Harbor was bombed. We were just through church, Sunday dinner and

dishes when someone turned on the radio. Within minutes we heard the

announcement that Pearl Harbor was attacked, with an undetermined loss of

lives and ships. Shock is too mild a word to describe our reaction. We

jumped into the car and went to Grandma and Grandpa Miller's house to share

our feelings and fear with the family. Grandma said, "It wasn't easy to go

through World War I and this will be even harder." Donald was already in the

Army and Buck joined the Air Force right away.

We soon found out what rationing meant. Sugar coupons were issued, and meat

and shoe coupons. Prices went up rapidly with many things becoming scarce or

impossible to buy. Gasoline and tires were rationed, as were cars and

machinery. Casey needed a tractor and traded our car for a small tractor and

a horrible old coupe. The car's doors flew open whenever they felt in the

mood! One day in Dupree, as I started home with the kids and groceries, Ann

leaned against the door and went flying out into the street, along with a

bottle of cooking oil. I rescued Ann first, but didn't waste any time

retrieving the scarce oil. Camera film was scarce and we got out of the

habit of taking many pictures. Our large, kerosene burning refrigerator

developed a leak in its cooling system. Sears informed us the factory had

been converted to war supply and there would be no repair. They did ask us

to ship it to them and paid us for the remainder of the warranty. A

gas-motored Maytag washer was purchased and was a lemon from the start. "War

conversion" was the excuse.

We began mailing cookies and candy to the boys in the service and doing all

we could to help supply our own families with food. Large gardens and

swapping with neighbors helped fill endless fruit jars. Since we could

butcher, we had meat, which town people envied, for when ration books were

used, they had to find substitutes. One neighbor made sorghum from cane and

we bought huge cans of it for sweetening. We bought Black Hills honey in 60#

cans to replace sugar. Mr. Voik had huge cornfields and let some of us

neighbors pick field corn to can. I recall driving up there about 4:30 a.m.

to get some to be able to finish canning it that day. One year Cully and

Margaret let us pick some string beans when they had an oversupply, and we

returned the favor the following year. When Margaret's washer broke down,

she brought her laundry and her kids to our house each week and washed

there.

Radio batteries were kept charged and saved for the news. The men worked

long hours raising wheat and cutting hay to feed cattle. There were no

bicycles or skates for kids at Christmas, and we had to hoard up our sugar

to be able to make a pan of fudge. Every family had someone in the service

and watched the mail constantly for letters. When it was rumored that Japan

planned to strike on American soil, Grandma Miller said she'd "throw her

flat irons at any that came into her yard."

Cloth became very scarce and of poor quality. Women made over large

garments into small garments. We answered an ad that was selling unclaimed

clothes from dry cleaners and laundries, and bought a package sight unseen.

It contained a faded woman's coat which I carefully ripped, turned the

bright inside to the outside, resewed it, and gave it to Margaret. It also

contained 2 or 3 silk or rayon dresses which I made into dresses for Marlene

and Ann .... and, several satin evening gowns, gawdy colors and cut on the

bias, which were totally unsuitable for children's clothes. These were later

taken to Cherry Creek where the Indian ladies grabbed them with glee. I

can't remember if we charged them a few cents, or what we did, but recall we

took eggs along to sell to them.

Art was in the Army and Verna and the girls came home for a visit. They were

at our house when Casey came from town to tell us he had received a telegram

notifying his folks that his brother Buck was missing in action.

Karen was a baby, and Butch Salisbury kept karo syrup under the counter for

baby formula, so she never missed a meal. Work, waiting, and worry became a

way of life. We learned to do without the things we couldn't get. Car

dealers had lists of people who wanted a car as soon as they became

available. When sugar was scarce, we learned to can with a lot less, though

at times a little extra canning sugar was allotted, according to the number

of people in the family. We ate well and really had no hardships, for the

wrecky old car got us where we had to go. Marlene learned to drive it at an

early age.

We had a lot of friends in town,, as well as relatives and neighbors in the

country who would gather at our place every Sunday, whether we had invited

anyone or not. I learned to make ice cream with sugar substitutes such as

honey, syrup and Eagle Brand milk. One Sunday, some regular visitors came

and stayed for the evening meal. I told everyone that I had experimented

with no-sugar chocolate and butterscotch sauce to put on ice cream. One man

was talking a mile a minute and spooning large amounts of what he thought

was butterscotch onto his ice cream. We saw that instead, he was spooning on

mustard, but everyone kept quiet. When he took his first taste, we found out

even though he was constantly playing jokes on others, he wasn't a good

sport when he was the victim.

Inez was teaching at a country school near her folk's place and invited

Dawn, Mary and Marlene to come to her Christmas party and program. The

cousins came to spend the night and Casey took them to the program. Dawn

looked over the audience and said, "I guess we're the dressed up ones

tonight!" The girls had a good time. When they got home I asked Marlene what

she had done. She said, "We heared them say pieces, and we dist crapped and

crapped'.....they clapped their hands!

In 1942 Marlene started school. She wanted to ride a horse the mile and a

half to the country schoolhouse, but I didn't trust horses. Casey took her

in the car most of the time. When she was older, she would walk to and from

school. One night she had a cousin stay with her. As I combed their hair the

next morning, I noticed both girls had little bugs crawling on their heads.

It was my first experience with head lice and I nearly flipped! I took the

girls to school and told the teacher what I had found. She began to examine

other children's heads and found that the whole school was lousy. The doctor

was gone so I visited a friend's mother to learn how to delouse a child. She

said, "Don't be so upset. It's no disgrace to get head lice --just a

disgrace to keep them." She told me to rub kerosene into Marlene's scalp and

comb her hair with a fine toothed comb. I did and Marlene's scalp blistered

and peeled, but the head lice left home.

All the neighborhood small fry were included in school parties and Christmas

programs. Marlene was proud as punch when her little sister, Ann, was big

enough to visit school.

When Ann was 5 months old, she became ill. The local doctor couldn't give a

diagnosis. We tried several treatments, but she refused to eat, had a high

temperature and was becoming dehydrated. As we were trying to decide where

to take her for a second opinion, a doctor from Pierre came to Dupree to

hold a tonsil clinic. He diagnosed Ann's problem as kidney infection and

gave her medication which made her improve almost immediately. As soon as

she was recovered we took a trip to Minnesota. My sister, Frances, had two

little girls for Marlene to play with and they had a good time. Myrtle and

Art always showed us a good time, that year taking us to see "Over the

Rainbow". Dupree only got OLD movies, so we were thrilled to see a newly

released, technicolor picture.

What courage - or blissful ignorance - it took to build a new house as soon

as World War II ended. I drew the plans, Casey hired a carpenter, and they

quickly streamlined my plan into a solid house with no frills. Ours was the

first new house in the neighborhood and we still owe a lot to brothers and

neighbors who helped. Since materials were horribly scarce, we had to reuse

lumber from the yellow house and the tarpaper shack, and nearly wore out a

car hunting other materials. Our furniture was all stored in a leaky,

mouse-ridden garage. We moved into a homemade trailer house we called the

white shack. I've tried very hard to shut that summer out of my memory, but

it keeps cropping up. A two-burner kerosene stove with a portable oven was

my only cooking facility. With a carpenter and his teenaged son added to our

family of five for meals EVERY DAY, I soon learned to cope. When threshers

and combiners came to work in the fields, I had to feed them on tables in

the yard. If Fred and Buck hadn't helped me, I would never have made it.

Every morning we got up early and I would start baking cakes and pies (with

sugar rationing! We were allowed 1# of sugar per person in the family for

nearly five years) and get the meat and vegetables started so things would

be ready by noon. Casey milked cows and we "separated" the milk out in the

yard, as there was no room in the white shack for the separator. The

separator "dishes" (parts that touched the milk) were washed, scalded,

covered with a clean dishcloth, and stored inside the little entry. The

girls were washed, fed, and sent outdoors, as there wasn't room to have them

inside unless they sat on the beds, which they had to do if it rained. The

threshers were usually 2 or 3 men with the rig (thresher) and several

neighbors and relatives, who would come to help, up to 10-12 men in all. It

took some men to drive hayrack teams, to pick up the bundles of grain in the

field, and haul them to the threshing machine: There, another team and wagon

waited under the grain spout. The wheat poured directly into the wagon box

and when it was full another team and wagon drove under the spout. The

loaded wagon (later trucks were used) drove to the town elevator to have the

grain weighed and sold. That summer the threshing machine broke down and I

had a crew of three repairmen plus two carpenters and our family of five,

for 2 or 3 days until the machine was ready to thresh again.

When the last load of bundles was being fed into the thresher at noon, Fred

and Buck hurried in, washed up and helped me set up two tables in the yard.

One was our table from indoors and was brought in after each meal. The other

stayed outside and had to be washed well before each meal. I would just fly,

getting clean dishes and silverware set out while the men helped carry out

the food. Some workers sat around the tables; the rest sat wherever they

could, but all ate heartily. When they finished the umpteenth cup of coffee,

Fred and Buck would help me pile dishes into dishpans and carry them inside.

I would rescue leftover food, wash dishes for an hour or so ..... then start

working on supper.

When combines were introduced in later years, they did the whole operation

mechanically, saving 6-8 hauling teams of men and a lot of the hand work.

Combine crews were smaller than threshing crews. They were usually

Southerners who followed the harvest from South to North until the season

ended. About three men came with the machinery, which cut the heads off the

grain, going around and around the field. At the same time, the machine

threshed the grain and put it into the hopper, a bin on top of the combine.

When the hopper was full, a truck was driven beside the combine, which

"augured" the grain into the truck. It was then hauled to town to sell, or

if the farmer wanted to keep some, it was hauled to his granary to store.

The trucker was usually one of the crew of Southerners, so the farmer rode

along to the elevator to watch the weighing and collect the money. The

elevator owner could short the weight and/or declare the grain a poor

quality and pocket the difference. Dishonest elevator owners were infamous

and the farmers had their own names for them. In one town, it was said you

were lucky to get your team and wagon back!

When the basement of the house had to be poured all at once, we gathered

relatives and neighbors to help. Midway through the day, they began to

insist Casey buy a case of beer to help get the job done. He couldn't leave

the cement job and I refused to go into a pool hall. Donald was working in

town, so I was sent in to get Donald to buy the beer and help me load it.

Just as he and I were heaving it into the back of the car, the minister of

our church arrived on the scene. He stopped to visit and I stammered and

stuttered the reason why I was buying 24 bottles of beer! One fourth of the

basement floor wasn't poured, and the upstairs wouldn't be finished until

the next summer as the carpenter had never done any plastering and wanted to

practice on his own, first. We decided to move into the basement at the end

of September. We had planned a gradual move, but three couples came out from

town and MOVED us one Sunday after church. With everything in boxes and

general bedlam in the basement, I realized I had almost 20 people to feed

for supper. We made it though.

We had the upstairs finished/painted, curtained and had lived in it only a

year or so when our lives changed. Florence came over to swap home

permanents one day, and as we prepared to start, a stranger knocked on the

door. He was an ASC official, who came to offer Casey the job of fieldman

for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. What a decision! Donald and Florence

decided to take over the ranch. We thought we would move into Dupree, as I

would be alone to haul school kids on winter roads while Casey traveled from

county to county. Rent a house in Dupree? You gotta be kidding!

We ended up moving to Spearfish where Casey had bought an old house. We

found out later it was not old, but ancient! The big bedroom was a tacked on

room, which sat right on the ground. The floor was terrible. There were big

double doors between the living room and bedroom which had sagged and didn't

close properly. I had no furniture for a bay window and one end of the

living room had a huge one. There were only two cabinets in the kitchen. The

dining room, which was almost too small and narrow to be called a room,

opened to outdoors - that is, the front door was in the dining room. The

bathroom was right beside the front door. The smaller bedroom opened into

the kitchen. The back porch where I had the washer, had outdoor vines

growing through the walls. The inside windows were seven feet high, and I

couldn't afford decent curtains.

Marlene was eager, but nervous, about starting a larger school. Ann and

Karen cried every night for six weeks to go back home. Casey was gone Monday

through Friday and I had no car. It seemed we got acquainted very

quickly for greenhorns, but that house was something else! When I discovered

my 36 quarts of home canned chicken and jars that held two home canned hams

had never been unloaded from the moving truck, I also was ready to "go back

home". It had all been stolen.

When Casey left one Monday, I called a realtor and discussed selling the

house. He had lived in town all his life and promptly told me the age, and

all the faults of the house. When I refused to sign a six-month contract, he

lost interest completely. The roof had to be repaired and Casey had it

stained, which made the house look better. We rented the upstairs apartment

to a family with four kids, two of whom wore cowboy boots. Overhead it came

through like a thunderstorm. We had advertised the house in the paper and

had 2 or 3 lookers who didn't like it, so I raised the price $1,000. Then

fortune smiled. As I answered the doorbell one day, a white haired, sweet,

grandma-type lady asked if the house was for sale. I assured her it WAS. She

said she had prayed for "just the right house and the Lord led me to this

one." They rented one large bedroom to us to store our furniture while we

built another house. As soon as school was out, we went back to the white

shack which sat in Buck and Eva's yard at Dupree,. It had been Florence and

Donald's first home too. The beginning of school found us renting a cabin,

in Spearfish, waiting for the last work on the new house to be completed.

Cully's oldest daughter, Eliza was staying with us making us an even half

dozen now.

We lived in our new house in Spearfish until school was out in 1952. Marlene

and Ann had learned to swim, play piano and had become city kids. We sold

the Spearfish house and were building the green house in Sturgis, but had to

rent a place for two months while the house was built.

We settled in before long, and when school started Marlene was a sophomore,

Ann in 7th grade, and Karen in 3rd. These were happy years with our kids,

other kids, and good friends.. Then, Casey's job got shaky and was brought

to an end with a new administration in Washington in 1954.

Everything happened at once that month. Casey had to have a tumor removed

from his back at the Deadwood Hospital. He was recuperating at home when he

was informed that his job was ending. To add insult to injury, the head

honcho from the state office was coming to Sturgis and asked Casey to meet

him at the airport. We felt obligated to invite the man for a meal, but it

was one meal I didn't prepare with TLC. I had my inning when I sent in

Casey's last weekly reports. When I addressed the envelope to this same

official, I substituted "S.B." for his first two initials, which were

"C.B."! It made me feel better, and we began to think of other things ...

mainly a new job.

At this same time, Casey and Ann wrecked the car. Ann was driving as they

hauled half a beef and several dozen eggs from Dupree to Sturgis. The roads

were rutty from a rain and she couldn't handle the car when it was caught in

particularly deep ruts. The car rolled over and over, eggs smashing and

coating everything. Casey laid blankets from the car seats out on the grass

over the beef, to keep it clean. People passing by thought it was dead

bodies. Casey asked Ann not to mention who was driving, so his insurance

would cover the wreck. She went to the top of the hill to warn other cars to

slow down, and a friend stopped, put her in the car and visited with her. He

was so nice she told him the secret.... it was the Sheriff from Dupree! The

windshield had been broken in the wreck. When Casey got ready to trade it

in, he and Marlene headed for Rapid City. It began to rain! They had to come

home to get cardboard to cover part of the windshield, leaving just enough

room for Casey to see to drive.

I had made up my mind the girls would go on to college if they wanted to,

and would have scrubbed toilets to see it happen. Casey was very fortunate

to stay with ASCS in the county office in Sturgis, and I got a job with an

optometrist. Marlene graduated in 1955 and went to college at South Dakota

State, to become a nurse. She married, her senior year. Ann was a junior in

high school, and Karen in 8th grade, and Casey wanted to move to the

country. We sold our green house and rented while we built a house 4 miles

from Sturgis where he had bought 60 acres. We moved into the new house in

July 1957. Casey got his job as fieldman back when the administration

changed again; the girls all grew up and left home. Ann went to Parks

Business College in Denver, worked there 3 1/2 years and married. Karen went

to Spearfish College for a year and then to beauty college in Rapid City,

where she worked awhile. She then moved to Pueblo, Colorado to stay with Ann

and Don. She met her future husband, married and moved to New Jersey.

On New Year's Day, 1969 we had dinner at Schnells. Mid-afternoon

we saw that a heavy snow fall had replaced the lighter snow that had been

falling all day. Hating to eat and run, we waited until about 3:30 and

started home. The storm had developed into a full fledged blizzard, and the

four miles home took a long while to negotiate. The storm continued through

the night. The next day brought worries of how Fred and the cattle at Dupree

were doing. Without a phone at the ranch to reach Fred, Casey called Buck,

who reported the weather was as bad there as in Sturgis. Roads would soon be

blocked if it lasted, as some already were nearly impassable. Casey's ASCS

job required him to travel to several counties a week. His schedule would

take him to Dupree the following day, so we packed a few groceries and

clothes and I decided to go along to see if I could help at the ranch.

Little did I know!

We were able to drive all the way to the ranch, though the roads were

especially bad from Newell to Faith, and the ditches were drifted full.

At the ranch it was decided I would stay and attempt to feed 52 head of

cattle, though I had never done that. Only the innocence of ignorance gave

me the courage.

Casey told me to feed hay twice a. day and cubes once a day, if we could get

the cubes to the cattle. The haystack was about half a mile from the house,

with four feet of snow on the level spots. All the earth seemed to be one

big white expanse, with only the ranch buildings and a few trees around the

dam to break the whiteness. It was 18 degrees below zero when Casey left for

another county office, and I was IT! He had warned me to never leave the

pitchfork at the haystacks, as it could drift under in Dupree's constant

wind, and there was no way for me to get another.

A pitchfork! Sure, I had seen plenty, but had little experience using one.

It became my cane, balance pole, hay thrower, and on one occasion I felt it

saved my life.

I bundled up in all the clothes I had along and pulled a pair of Casey's old

wool pants over my slacks, then put on his heavy old parka. I found the best

foot gear (lightest and warmest) was heavy socks, then tennis shoes, more

heavy socks over the shoes, and a shiny new pair of men's four-buckle

overshoes over everything. Casey and I thought the overshoes were his, but

they later turned out to be Fred's new Sunday best. At the time I was too

concerned with just survival to worry about the details. Finally, dressed

and full of breakfast, I started out. I was soft as mush, and that was the

last time l ate BEFORE tackling that long walk and hay throwing. I had two

pairs of men's work gloves on, with the cloth pair inside for warmth, and

the leather pair on the outside to stop the wind and take the abuse of the

hard work. I wound one oversized hand around the pitchfork and with the

other grabbed a small pail of cubes .... and headed "north". Even direction

was uncertain in all the whiteness.

The cattle were scattered between the buildings and the pasture, looking for

shelter from the cold wind. Rattling the cubes in the pail and calling like

an old cow hand, I got them started following to the haystack. Their round

feet made a track much shorter than my feet but I felt I had better follow

their winding trail. Several days of walking in their steps made the ends of

my toes as sore as boils. Leaving their path, I would flounder in the snow

up to my knees, and it was easier to have sore toes than break my own path

each day. Though each night's snow or wind filled any tracks, the cattle

followed the same path each day and it could be found by its roughness. When

we got to the haystack, I wondered how I could possibly obey the order "feed

from the top of one end and keep the stack as whole as possible", when I

couldn't possibly climb it...too tired, too many clothes and too cold!

Darned if I would admit I couldn't do it! The pitchfork was a good climbing

pike. Once on top, I had to learn how to dislodge a heavy, snow-covered bale

of hay and push it to the ground. How many did he say to feed each feeding?

I think it was 10 or 15, but will have to ask Fred if I ever get back to the

house. I had to cut the baler twine. Casey had given me his knife and if my

hands hadn't been so cold, cutting string would have been a lot easier.

Next, I knew I had to break the bale in two. Jackie Birkland once told me

she could throw a one hundred pound bale over the fence, but I knew I would

have about all I could do to lift half a bale. Now, jab the fork into the

hay, stumble to the fence and heave it over to the cattle. Casey said to

scatter them so all could get at it, which meant trying to aim them when I

could barely lift them. Finally the stupid, fighting critters were all busy

eating, the quota had gone over the fence, and I could struggle back to the

house to get warm. Some days the sun shone and some days it was snowing and

blowing, as cold as Siberia. It was always a good feeling to know I had fed

one more day, and the exercise was making the strenuous work a little easier

each day.

When I first was at the ranch, relatives came to chat, drink coffee and have

dinner. After a few days of this, provisions were dangerously low and I had

no way to get to town. I finally had to tell them I had no more to share and

as the roads got deeper each day, the visits dwindled to just an occasional

visitor.

Casey always worried about the way things were being done. He was afraid

that the calf crop would be hurt. When roads became impassable, he bought a

snowmobile. He made a toboggan from an old car top and could haul hay bales

on it.

Two cows got sick. One had dysentery and the other had bad feet. I named

them Footsie and Shootsie, put them in the barn and carried buckets of water

and hay to them.

Each morning as I would leave the house Fred would say, "Its too dangerous

to go feed! We won't see you again if you go." It became a ritual, sometimes

repeated at the late afternoon feeding also.

Casey brought what food he could haul on the snowmobile, weekends, but we

didn't have many extras. After about 2 or 3 weeks there was a lull in the

weather. The snow plow had cleared Cherry Creek Highway, about 3 miles from

the ranch, and Donald and Marvin drove out. After feeding them the best I

could with the limited supplies, I asked to ride back to Sturgis, knowing

Casey would be there.

Back in Sturgis, Casey and I went to town and bought groceries. We loaded

the pickup with them and added a lot of meat and canned goods from our

basement. Casey drove me back to Dupree. I made a cache in a deep snow bank

just north of the house to store the frozen meat and vegetables. A day later

I looked out the living room window and smack dab on top of my food cache

Fred had tossed 3 or 4 dead, bleeding rabbits he had shot. He was quickly

persuaded to move them!

Fred's cattle were suffering. He and Clint would try to feed them, but only

part of the herd was ever near enough the haystacks to eat. To get corn or

cubes to them, Fred would catch a ride to Dupree, hire the snow plow to make

a road to his place and have a trucker follow the plow with some feed.