A short while after I was born, Dad

brought his friend, Ed Kramer, to see the new baby. Ed, knowing that Dad

was proud of his Irish heritage, said, “Walt, that kid has the map of

Ireland on his face . . . you should name him Casey.” The name stuck all

through my life, and more people have called me Casey than have ever

called me Walter. This had one advantage, as the family didn’t have two

Walters, to add to the confusion of a large family.

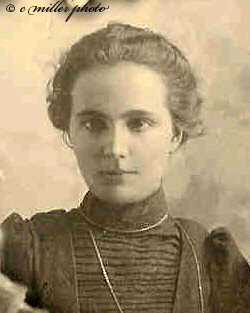

1910 was one of the driest, worst

years the country had ever experienced. Dad heard about a big dam being

built on the Missouri River, at Great Falls, Montana. He headed west,

and worked there for several months. He also worked for a time in

Canada. Mother kept the home fires burning, caring for the new baby plus

four older children, two boys and two girls. I remember Mother telling

how hard it was to feed the family on

the little money Dad was able to

send home. Codfish was cheap that winter, and our diet consisted mainly

of potatoes and codfish gravy. Mother was the greatest! We kids

certainly thought so, and all who knew her said she could prepare good

meals for her family, which eventually numbered nine children, on next

to nothing. She was filled with all of the compassion and loving

kindness needed to hold a large family together. How great are the

memories of our Saturday night baths, when she put all of us through the

warm water in the old washtub and then stood us on the oven door of her

old cook stove while she rubbed us dry. I can still see her standing over

that old wash tub, the sweat dripping from her face, washing clothes for

the family of eleven, on the washboard. She worked so hard but never

complained. What a story her life would make!

the little money Dad was able to

send home. Codfish was cheap that winter, and our diet consisted mainly

of potatoes and codfish gravy. Mother was the greatest! We kids

certainly thought so, and all who knew her said she could prepare good

meals for her family, which eventually numbered nine children, on next

to nothing. She was filled with all of the compassion and loving

kindness needed to hold a large family together. How great are the

memories of our Saturday night baths, when she put all of us through the

warm water in the old washtub and then stood us on the oven door of her

old cook stove while she rubbed us dry. I can still see her standing over

that old wash tub, the sweat dripping from her face, washing clothes for

the family of eleven, on the washboard. She worked so hard but never

complained. What a story her life would make!

When we were small, our main

playground was down by the slaughter house, about two blocks east of our

house. The town butcher did all of his butchering in an old unpainted,

frame building. It had a plank floor with a trough that carried the

blood and waste into a small pond. I liked to watch the butchering, and

he liked kids, so we were buddies. The dirty pond served as our swimming

hole in the summer and skating rink in the winter. I always went

barefooted when there wasn’t snow on the ground (and sometimes when

there was), and would come home with blood and animal hair covering my

feet and legs. Mother would bring out the tub filled with water from the

reservoir of the old cook stove, and clean me up. She never scolded me

for it.

One time, when I was about 5 years

old, I decided to check on the spring runoff at the pond. I took my

oldest brother’s knee boots which came up above my thighs as Cully was

10 years older than I. The deepest part of the pond came right to the

boot tops, and of course that was where I wanted to go. All of a sudden,

I stepped on some ice on the bottom. My feet flew up and I ended up

sitting in the icy water, up to my neck. I got out of the pond and

started to run for home, following the railroad tracks. My older

brothers were looking for me, and found my trail. The weather was very

cold and I left a footprint of ice on each railroad tie as I ran. When I

got home, it was back to the oven door and a good rubdown from Mother.

All of the town kids played along

the railroad track. The older boys kept their tobacco and cigarette

papers hidden between the timbers under the railroad bridge. I felt

really grown up when they let me follow them as they went for a smoke,

and never squealed on them.

We had an old cat we called Muver

Cat, as she always had a litter of kittens. One of my best friends was

the middle-aged manager of the grain elevator, Bill Maier. He was

bothered with mice and wanted to buy Muver Cat. We made a deal – he paid

me 5 cents and I delivered the cat. The next day the cat came home, so

we made another deal – another 5 cents and I delivered the cat. I don’t

know how many times I sold him the same cat, but I heard Mr. Maier

joking with my dad about it one day. This was my first experience with

the profit system. My family has kidded me that some of my present

savings started from the profit made selling the old cat.

Our family had some very good

friends, Schulers, who had about the same number of kids as we did, and

all about the same ages. Their boy, Howard, was my age, and I spent a

lot of time staying at their farm which was 6 miles north of town. They

had a team of white mules we could ride plus many other animals we

played with. One time Mr. Schuler came to town with a load of wheat in a

high wagon, pulled by the white mules. I decided to go home with him but

didn’t want to ask Dad and chance being refused. I waited until Mr.

Schuler started down the road for home, and walked behind the wagon

where he couldn’t see me. When we arrived at their farm and I made an

appearance, he said, “Where did you come from?” I confessed to following

him home, and he called the folks. Mother and Dad had missed me and

alerted the whole town. They were quite relieved to find out I was in

good hands. After a few days I returned to town when Mr. Schuler took

the next load of wheat to market.

When my little 5 year old friend,

Oscar Brandt, started school, I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t go as

I was also 5 years old. There was no kindergarten in those days. I

followed Mother around the house coaxing, for several days. I explained

that I could already read. I had a primer I had received for my

birthday. I read it so much the pages had turned black from dirty hands

and I could recite parts of it from memory. In one of her weaker

moments, while she was trying to wash clothes with me tagging her,

begging, Mother said, “Alright. You can start, but don’t come around

asking to quit if you get tired of it!” I solemnly promised I wouldn’t.

However, after about a week of having to sit still in school, it got

old, and I wanted to quit. Mother ignored my protests and I was on my

way to an education.

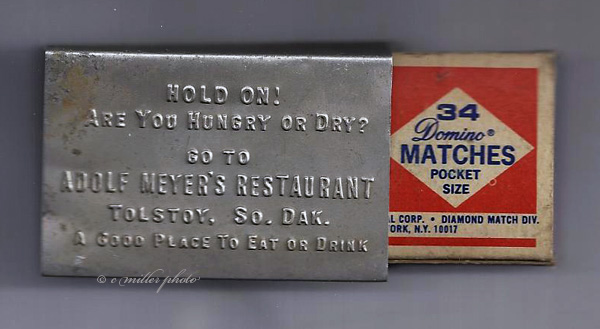

When I was about five years old, a

circus came to Tolstoy. They set up the big tent, and staked out the

animals near the old slaughter house, our favorite playground. Since

this was definitely an invasion of our territory, we felt the least they

could do was to issue us free passes. When we presented them with our

proposition, they agreed to give a free pass to anyone who would take

the horses to the town well, and water them. I took the job. Our house

was about halfway between the circus and the town well, so after the

ponies were watered, I decided to show off a bit by riding one of them

past our house. I had never tried to ride a horse before, but I got on a

mare who had a little colt following her. With only a halter on the

mare, I couldn’t have controlled her even if I had known how to ride. She

ran, frightening the colt, who ducked under our front yard fence. Dad

managed to get the colt out and back onto the road without it getting

wire cuts, and I managed to stay on the mare’s back. When I got them

back to the circus grounds the caretaker told me I shouldn’t have done

it because they weren’t broken to ride.

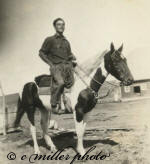

My next riding experience was the

summer I was six. I thought I was old enough to ride and walked to Aunt

Annie and Uncle Christian’s farm, about a mile northwest of town.

They had a driving mare named Pride they used to pull their top buggy,

which was very modern transportation at that time. After considerable

coaxing, Uncle Christian saddled the horse and I started for town to

show off to the other kids. Pride was high spirited and ran so fast I

fell off, going top speed. She stopped and waited for me, but I decided

I wasn’t quite ready to be a cowboy and I led her home.

and walked to Aunt

Annie and Uncle Christian’s farm, about a mile northwest of town.

They had a driving mare named Pride they used to pull their top buggy,

which was very modern transportation at that time. After considerable

coaxing, Uncle Christian saddled the horse and I started for town to

show off to the other kids. Pride was high spirited and ran so fast I

fell off, going top speed. She stopped and waited for me, but I decided

I wasn’t quite ready to be a cowboy and I led her home.

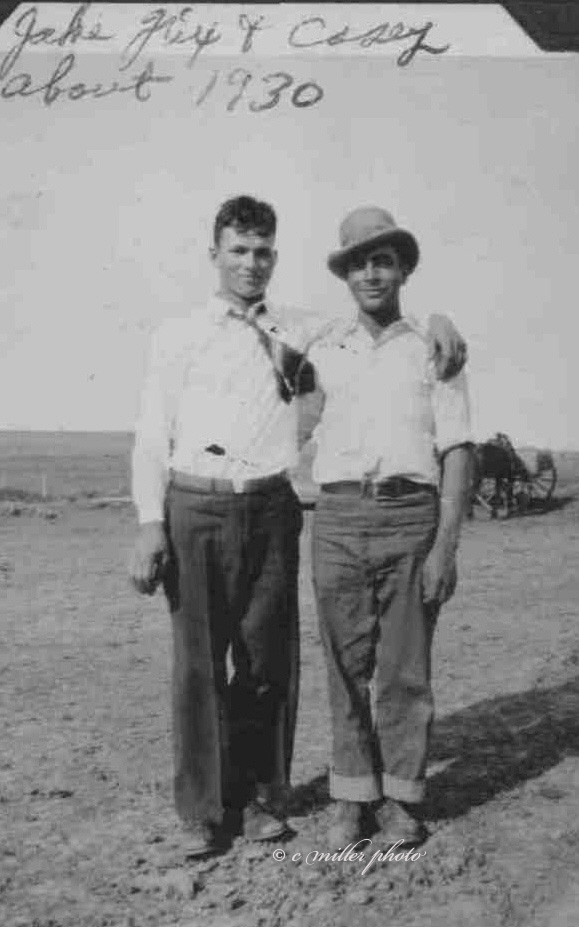

The same summer, my chum, Harlan

Bitzer, and I got into trouble for stealing vegetables from a widow

lady’s garden. Her garden was about a block from her house, and we

didn’t think she could see us as we each pulled a juicy turnip. Imagine

our shock when we looked up to see her bearing down on us, looking

mighty angry! We dropped the turnips and ran, making a wide circle to

lose her, and hoping to get home as fast as we could. As we glanced over

our shoulders we saw that she had stopped in at Harlan’s home and was

talking with his mother. Changing plans, we ran and hid in an old barn

just across the street from my home. Here we could peek out a small

window and see the widow and Harlan’s mother coming to our house. Mother

was out in the yard and although we could see them talking, we couldn’t

hear what they were saying. We know what they were talking about though,

and stayed in the barn all afternoon. When it started to get dark we

knew we had to go home and face the music. Mother didn’t spank me, but

she really gave me a lecture. She said “Mrs. Bitzer told the widow lady

that she knew Harlan would never steal vegetables, but I told the lady I

wouldn’t put it past you.”

A friend of Dads had a big steam

threshing machine he had to move from the job he had just finished to

another farm several miles away. His crew wasn’t available on Sunday, so

he asked Dad if I could drive the mule team on the water wagon and

follow the machinery. Dad said sure, and off I went on my first job. The

man started the steamer, hitched the mules to the wagon, and handed me

the lines. I told him I had never driven a team, but he assured me, and

rightly so, that all I had to do was sit on the seat holding the lines,

and the mules would know what to do. As I remember, about all I got for

pay was a new nickname. The one who hauled water was always called the

water monkey . . . and “Water Monkey” I was, from then on. The summer I

was 7, I decided I was ready for steady work and got a job driving

header box for a big wheat farmer, Howard McKray. My pay was $1.50 per

day, which was good pay because it was during World War I, and times

were booming. Also, I was experienced, having driven the mules the one

day, the summer before! The job lasted about three weeks and everything

went well except I went bareheaded. My hair was clipped short, right

down to the roots, and the sunburn I got really peeled my scalp.

I don’t remember too much about my

first year of school. Luella Nold was my teacher, and we had 6 month

school terms in a little one room shed. There was a pot bellied stove in

the center of the room and a double row of seats and desks along one

side. The teacher’s desk sat at the front, with a large blackboard on

the wall behind her. There was one long seat beside the teacher’s desk,

were she held classes. We always listened to the class one grade ahead

of us and the next year would be able to answer most of the questions

without studying. I remember one day a little guy wet his pants while

writing at the blackboard. He was too bashful to ask to leave the room.

The outhouses were so far from the school house he probably wouldn’t

have made it anyway.

My second year of school was taught

by our first grade teacher’s sister. I remember we got some new books

that year so our knowledge from listening to the grade ahead of us the

year before didn’t help too much in those subjects.

That year, on Halloween night, we

followed the older boys to Dad’s pool hall, the gathering place for

young and old. Harlan and I were still chums and decided that if the

older boys could pull Halloween pranks, so could we. There was a cream

station on Main Street, with about 30 empty cream cans in front, waiting

for their owners to come pick them up. We thought they would make a good

barricade across Main St., to stop traffic. With no streetlights, we had

to wrestle the cans in total darkness, and they were heavy for small

boys to lift. We finally had all of them in a line across the street in

a very effective barricade. Just as we finished, we were each seized by

an arm, and a gruff voice said, “you boys are going to jail for this!”

Horrors! The town marshal, Mr. Shortsman had appeared out of nowhere,

and had us in a firm grip. The jail had always spooked us, just to look

at the outside of the gloomy brick building, with bars on the windows.

Imagine what the inside must be like! The terrifying thought made me

nearly collapse in utter panic! Harlan and I must have been thinking the

same thoughts. We both lunged out of the marshal’s grip at the same

time, and ran as fast as our trembling legs would take us, straight for

Dad’s pool hall. Gasping for breath and shaking as we had never shook

before, we shot into the pool hall and asked Cully, Fred, and Harlan’s

oldest brother to hide us so we wouldn’t be sent to jail. Cully, always

the brave one, and not having any love for “Old Shortsman”, as the older

boys called the marshal, told us not to hide. He said, “Stand right

here, and if he touches either of you, we’ll bust him.” Mr. Shortsman

walked past the pool hall without a glance in our direction. When the

coast was clear, I scurried off through the darkness, wanting to get

home as fast as I could, and escape any more threats of doom that night.

For quite a few days, Harlan and I didn’t go downtown, and only when we

heard the marshal was out of town, did we feel really safe venturing

onto Main St.

My next teacher was a small Irish

girl, Miss Agnes Carr. She was a good teacher, but very strict. When we

were dismissed we would march out single file and were supposed to be

very quiet. Some of us were so glad to be dismissed that we would let

out a loud yell as we reached the door. One day she slipped out ahead of

us and stood by the door. When I came out with the usual YAHOO, she

grabbed me by the neck and flopped me onto the step. That was all it

took . . . no more war hoops. Her brother-in-law worked in the garage

and eventually, he seemed to learn of each prank I tried to pull. When

he would mention one of them to Dad, I would get a second punishment

when I got home.

The next school year was great! The

district built a large, two room building. One room was 1-4 grades, and

the other was 5-8. The rooms were divided by a large hallway where we

hung up coats. Overshoes and lunch pails were stored on the floor under

the coats. The thing that made this year so great however, wasn’t the

new building. It was because I had a secret crush on the teacher, Alma

Glanzman. She later became Mrs. Harold Bitzer . . .only because my love

was too good a secret! She is still living in Tolstoy now, 67 years

later. I visited her in 1981 and she still looked good. As I was

leaving after our visit, her eyes twinkled and she said, “Casey, you

were a little devil in school.”

In the summer of 1919, Dad ran the

Overland Garage and sold Overland cars, plus had a repair shop. He had a

large office where a lot of people gathered in the evenings. Here the

older town boys would get us smaller kids to wrestle and fight to

entertain them. Some of the battles got savage, and I would give up

before I would draw blood on my best friends.

In the summer of 1919, Dad ran the

Overland Garage and sold Overland cars, plus had a repair shop. He had a

large office where a lot of people gathered in the evenings. Here the

older town boys would get us smaller kids to wrestle and fight to

entertain them. Some of the battles got savage, and I would give up

before I would draw blood on my best friends.

Our friends, the Schulers, bought a

home in Aberdeen, and Mrs. Schuler and the children moved there for

school. My oldest sister, Eunice stayed with them and attended school

until she got her teacher’s certificate. She then began teaching school.

I visited my friend Howard occasionally, and got some city experience.

The older boys wanted to farm, so

Dad sold the garage and we prepared to move onto a farm. All of us were

very excited about the move. Dad started going to auction sales to buy

machinery and livestock. The greatest purchase was a half-Shetland pony,

one year old, named Buster. Dad intended that Buster be my pony, but he

held back giving him to me, just to tease me. A farmer near town had

given me a runt pig for helping him, so I figured the best way to get

the pony would be to trade Dad the pig for him. One day I thought Dad

was in a good mood, so I propositioned him. “Dad, I’ll trade you this

pig for Buster.” Dad grinned, so I said, “Okay, Dad. The pig is yours!”

Dad, being an old horse trader, thought that was pretty good. I heard

him telling his friends and having a good laugh. Buster was badly

spoiled and would kick and bite us every chance he got. We lived on the

old Nelson Place, about a mile northeast of town. I thought I would ride

him into town to show off a little. He behaved pretty well until we got

right in the middle of Main St. . . . and then bucked me off in front of

several people. I was never so embarrassed in my life! I had to turn him

over to my older brothers who finally got him well broken. All of us

younger kids learned to ride on him. He was the greatest pony ever.

We lived on the Nelson Place in

1919 – 1920. We walked to school in town. It was a very hard winter and

my job after school was to fill all the horse and cow mangers with hay

from the big hay mow above the barn. I would go to the pig pens and pick

up corn cobs for fuel, after the pigs had eaten the corn. In the middle

of winter we moved to another farm Dad had rented, about 8 miles

northeast of town. It was later known as the Dickhaut Place. The move

must have been a terrible job for the folks and older boys, as the snow

was deep and the weather extremely cold. They moved the livestock and

machinery first, followed by the small amount of furniture and household

things we had. We kids all had the flu. Mother packed bedding around us

in Dad’s old Overland car and we drove to the new place. Dad had hired

on old Swede, Gus Nelson, a bachelor who was a carpenter, to help fix up

some of the buildings, and he had a good warm fire in the stove when we

arrived. It felt great. Mother fixed a warm meal and we settled in.

School was a problem as it was January and we were 4 ½ miles from the

nearest school. The older boys fixed up a light sleigh which I drove

with an old roan team of horses, Sam and Dick. They were a great team,

but the winter was so severe we missed a lot of school – so much, that

if I remember correctly, I had to repeat 4th grade. Perhaps some of the

other kids had to repeat also. Our teacher was Miss Black, but she must

not have impressed us much as I can’t remember anything about her.

When school was out, our first

spring on the Dickhaut Place was great. We had a lot of little calves,

pigs, colts and a good crop of kittens. My little brothers, Donald and

Delbert, informed Dad that if he would raise the calves and pigs, THEY

would take care of the kittens. One morning Delbert got up early to

check on the old cat to see if she had her babies. He ran back to mother

at the house and with a big grin, stuck up two fingers. “Two hes.” Then

he stuck up three fingers, “And three shes!”

Everyone from my little sister

Verna, on up, helped Mother and Dad hand milk about 30 cows. We sold the

cream and fed the skim milk to the pigs. Dad said we didn’t make much

money as cream was so cheap, but we didn’t have any time to go places

and spend money anyway.

It was my job to feed and water the

pigs. It seemed all 150 of them would try to be the first at the trough.

Their sharp feet really hurt when they stepped on my bare feet. My older

brothers and Dad used horse power to do all the farming. I would get up

early and ride Buster to round up the horses and milk cows. One not so

pleasant memory is herding the cattle one mile south, on an old vacant

farm, the Anderson Farm. I would ride Buster over in the morning and

have to stay until evening milking time. They were long days! The vacant

buildings were spooky and the area scary for a 10 year old boy. My older

sister, Hazel, would go down with me occasionally, for company. One day

the neighbor’s big black bull got out and came near us. He was roaring

and pawing, scaring us half to death as we were sure he was after us. He

only wanted to fight with our bull however, and never hurt us. We all

worked hard, but we had fun too. After the chores were done, we played

with our pets and played baseball. One evening Hazel and I were having a

cricket game. Hazel had new glasses and didn’t want them broken, so she

took them off and laid them on the ground. After the game was over, she

discovered she had stepped on them. They were broken and she had to get

new ones.

Every spring a great migration of

birds flew over our farm. We enjoyed watching the ducks, geese and

cranes flying overhead. The cranes would stop and feed in our corn

field. It looked as though the whole field was carpeted with cranes.

A man was drilling a well for us,

using a drilling rig powered by one horse. He liked to hunt and kept his

loaded shotgun beside him. As some geese flew over, he shot and crippled

one. It came down about ¼ mile west, so he unhitched the horse from the

rig and rode over to get it. He had quite a chase to catch the goose,

but Mother fixed us roast goose for dinner.

During this summer I noticed that

Mother was more tired than usual and would lie down to rest between

jobs. On the bright morning of May 15, 1921, we woke up to a baby

crying. A country doctor had been called, but we kids slept right

through it all, and didn’t know until morning that we had a baby sister,

Inez. The next day complications set in and Inez would have bled to

death if not for the help of a neighbor lady, a midwife, who came over

and helped her. She was a skinny little baby at first, but after a few

weeks of Mother’s loving care, she was a cute, plump little one.

The following winter we were able

to attend a school only 1½ miles from home, taught by Mrs. Binder.

Hazel, Verna, Donald and I drove horses and occasionally we would have a

race as we were headed home. One day, in a hotly contested race, some of

the tugs came unhooked and the sleigh tongue dropped down which scared

the team so much it started a runaway. Hazel and I both pulled on the

lines for all we were worth, until they pulled us over the front of the

sleigh. I don’t remember how Verna got off, but the team was running

away with Donald sitting in the back of the box. I was scared the sleigh

would roll over with the tongue dragging in the snow and the team

running full speed. I ran behind and yelled for Donald to jump out. That

was expecting a lot for a little 6 year old, but he crawled over the

back end gate and his feet hit the ground just as he let loose with his

hands. I was so relieved he hadn’t been killed even though blood gushed

from his nose as his face hit the frozen ground. Since both sides of the

road were fenced, the team couldn’t turn off. A neighbor came down the

road and stopped them. We hitched everything back up, got in and drove

home. We were lucky no one was seriously hurt. Donald had a sore nose,

but he was a tough little guy.

Delbert was too young to go to

school, but nearly every day as we came home, he would be riding Buster.

He was so tiny that he looked like a horsefly on Buster’s back. He

always had a handful of mane and his toes sticking right into Buster’s

sides, to keep from falling off.

When spring came we had a lot of

fun along with the hard work. Verna was small, but she could milk some

of the 30 cows as fast as anyone. She was a tomboy and tough as any of

the kids. Dad bought us a set of boxing gloves and she would stand toe

to toe to slug it out with any of the boys.

We liked to catch gophers and would

set traps on the school ground. We would watch them from the window

during school hours and whenever we caught one, we would ask to leave

the room, kill the gopher and reset the trap. We were lucky and didn’t

get caught. We played baseball and raced horses on Sunday. Buster could

beat most of the other horses even though he was small.

With fall came my 5th grade in

school. I was getting older and more serious about school. The farm we

lived on was sold so we moved in the middle of the winter to a farm one

mile west known as the Sam Wise Place. It was only ½ mile to school so

Sam and Dick got a well deserved rest while we walked. We all did well

in school and competed with other schools in the spelling matches or

spelldowns. Hazel and I used to stay up late at night drilling each

other. She won all the matches in her grade, but I had one girl in the

area I couldn’t beat. We pulled a few pranks that year that we shouldn’t

have done. One kid brought his 22 caliber rifle to school and kept in

the barn so we could target practice during recess. Thank the Lord one

kid squealed on us before anyone was hurt. The teacher took the gun

until the end of the year. We boys all wanted to be cowboys and would

take some of the horses out of the barn during recess and buck them. We

never got punished for that. I guess the teacher thought that was mild

compared to what we could have been doing. I remember one boy, whose

parents were about to have the bank foreclose on all their livestock,

who used to get us to make his horse buck. He’d say, “Give her hell,

she’s the banker’s anyway!”

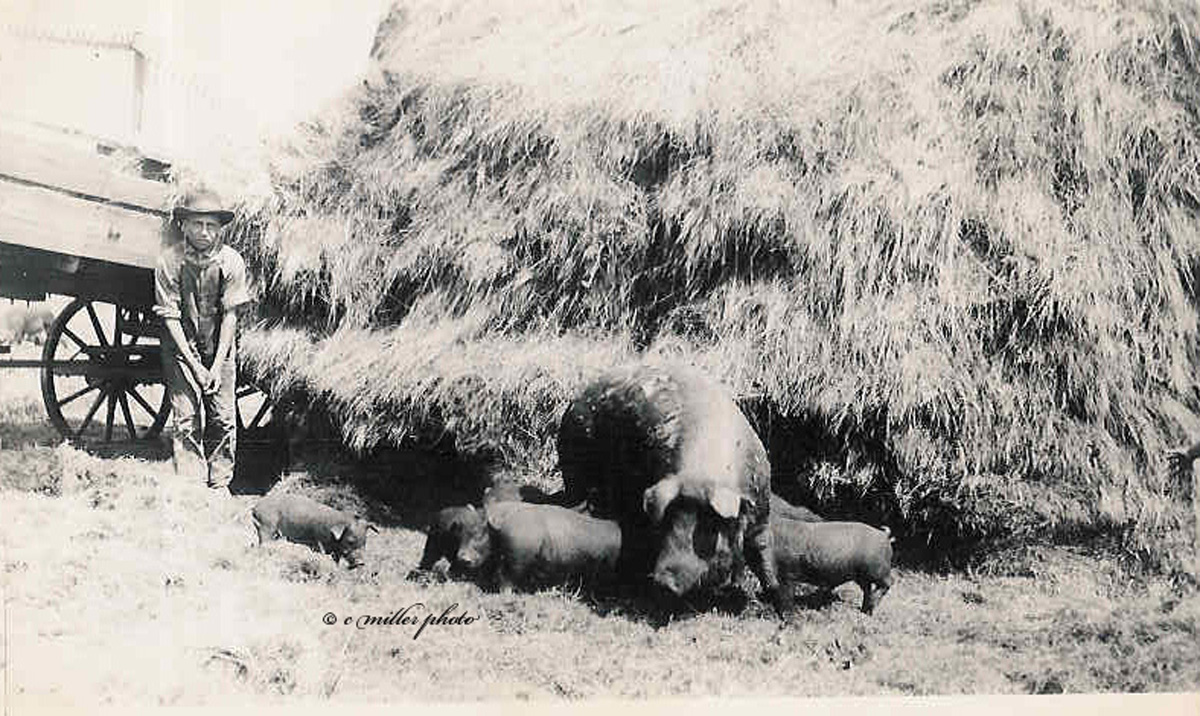

A neighbor who had fancy, purebred

hogs, asked Dad to sign me up in 4-H with his son.

The nearest club

was

at Hoven, South Dakota, 15 miles from home. I would ride Buster to the

neighbor’s house and go to the meetings with them. The banker in Hoven

was our leader. I purchased a registered Duroc Jersey sow with fine

breeding and raised a litter of pigs from her. After giving them the

finest care possible, I took them to the club show and won first place

with a litter of four. I earned a trip to the South Dakota Sate Fair,

but we were so poor and busy I didn’t get to go. I didn’t say much about

it as I didn’t want Dad to feel bad because he couldn’t send me.

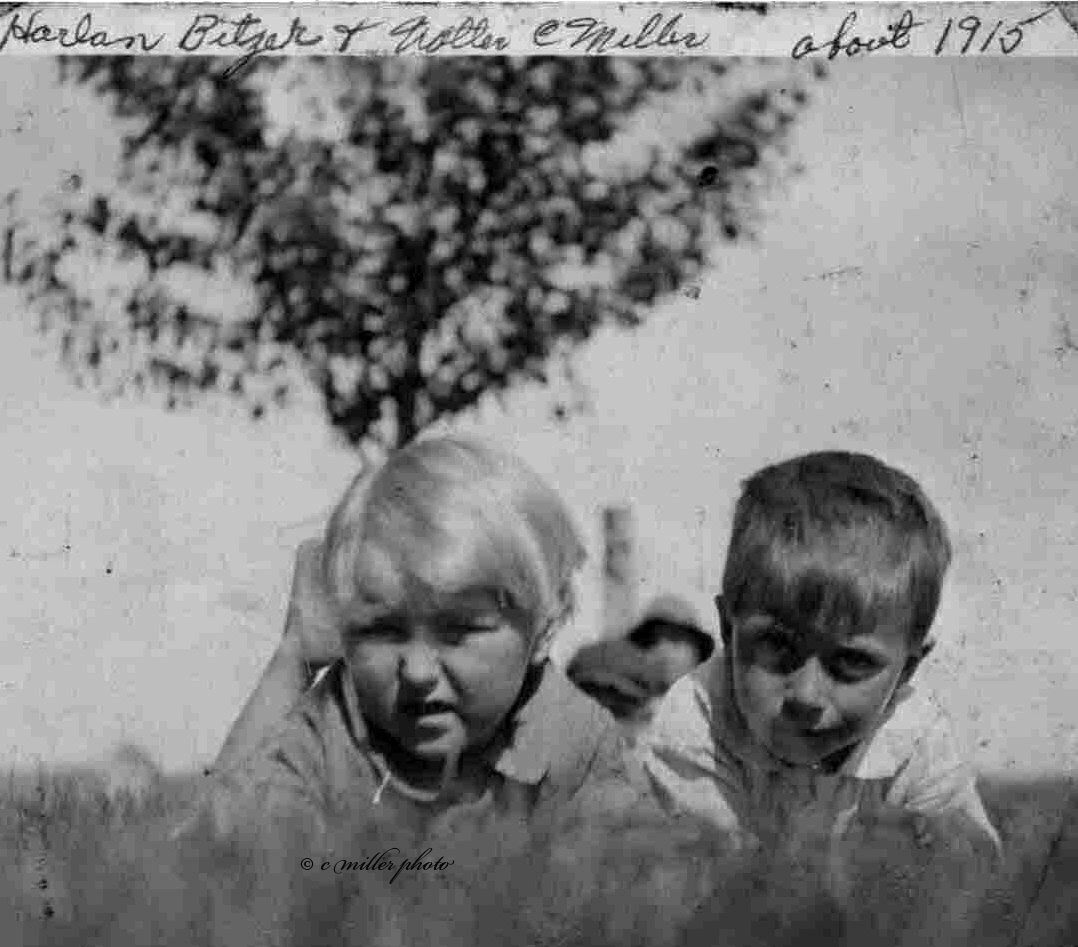

Click to enlarge all pictures

1921 wcm as marked is Casey

1922

Casey and his pigs

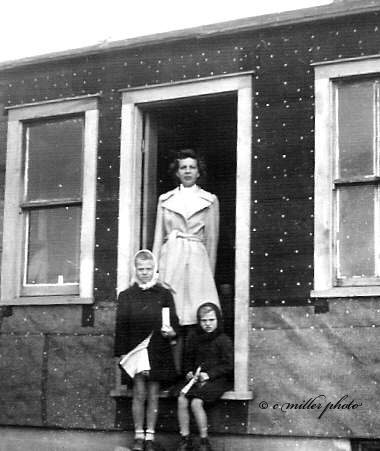

Eunice was teaching a rural school

about 4 miles east of home. To get to school, she drove

a two-wheeled cart with large wheels

pulled by a black mare

named Flip. She taught and even

did her own janitor work, all for $40 a month. The winters were

extremely cold, but she was hardy and hardly ever missed a day.

We missed Mother terribly for a few

weeks while she went to St. Luke’s Hospital in Aberdeen to have a very

large tumor removed from the side of her face and neck. Medical science

left a lot to be desired back in those days and the surgery left a big

scar and paralyzed her face from the severed nerves. She was unable to

close her left eye and her face sagged badly from then on. The family

felt sorry for her as she had been a very attractive lady. She never

complained and took over the family duties my sisters had handled while

she was hospitalized.

School was late getting started the

winter of 1922 - 23 because the school board had difficulty finding a

teacher. They finally hired Bill Keen, a strapping 6-footer from

Minnesota. Our school had a couple of boys about as big as he was, and

he was just what was needed to straighten them out . . .and straighten

them out he did! I don’t remember a single prank we pulled as we put too

much value on our lives. I loved Mr. Keen and learned more that year of

6th grade than any other year in school.

Dad rented a tract of land about 6

miles northeast of our farm during the summer of 1923 for putting up

hay. We pitched a tent up there and some of us stayed in it to care for

the horses. Dad was quite a horse trader and dealer, so we were always

using wild, spoiled horses. One day I was raking hay with a young,

half-broke blue roan mare and another spoiled blue roan mare that hadn’t

been broken until she was 8 years old. The flies were bad, the horses

started kicking and running, and I had to roll off the seat backwards to

save my neck. The horses ran toward home and I was afraid they might run

over some of the younger kids while they played in the yard. I ran all 6

miles behind them, and was very relieved when they got tired and slowed

to a trot before getting to the yard. It was amazing that they ran

through four open gates, pulling a 12 – foot rake, and never even hit a

gate post.

The 7th grade was a hard year and

took a lot of work. Our teacher, Miss Rostimily, had very little

discipline and rarely came out of the school house to the playground.

The big boys disrupted school and we had a lot of wrestling and fighting

out in the barn during the noon hour which left hard feelings between

some of the boys.

At home we had some fun and

excitement when Dad traded for a couple of broncos. Fred and I decided

to break them to ride. The snow was belly deep when Fred snubbed them to

the saddle horn of his gentle horse and took them to the field where we

mounted them. We rode several days before I decided the meanest one was

safe to be taken out alone. When we got out of the deep snow he really

took to me and bucked me off hard. At 13 years old I wasn’t quite ready

for anything that rough. Dad saw it and got angry. He said, “Bring that

SOB to me, and I’ll ride him.” He did, but it put him in bed for a week

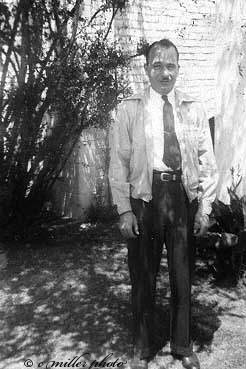

with appendicitis. Dad was a small man in stature, but had a lot of guts

and would tackle anything if his Irish got up. He taught us the art of

dealing and not to be afraid to tackle anything that comes along.

Times were tough and we didn’t have

the money for the bicycle I had always wanted. One day I heard of a man

who had an old broken down one, so I hitched old Maggie to the two

wheeled cart and drove about 8 miles south to his place. The bike didn’t

have tires and some of the bearings were gone, but he sold it to me for

$2.50. When I got home, my oldest brother Cully said, “Where did you get

that junk?” I was highly insulted and said, “I’ll have you know that

isn’t junk!”, and began to work on it. I fixed the bearings and took

some of Dad’s big 1-inch rope to tie on for tires. I could ride it but

it rode very rough and pedaled hard. We were so busy there wasn’t much

time for riding anyway.

One day, after milking, I was

carrying two 5-gallon pails of milk to the house. No one was in sight

as I passed the bike and I thought, “Now is my chance!” The bike wobbled

when I got on and spilled both pails of milk just as Dad and my brothers

came around the corner. I wanted to disappear, but had to face them for

the dressing down.

The county was paying a bounty on

gophers. I trapped a lot, but wanted a rifle so I could shoot more of

them. After several weeks of coaxing, the folks didn’t tell me, but

ordered a new single-shot Winchester 22 rifle. What a wonderful

surprise! Jack rabbits were plentiful and worth good money, so the rifle

paid for itself in a short time. I shot and trapped fur bearing animals

and from then on bought all my own clothes from the income. Skunks

presented a special problem. The school teacher didn’t much appreciate

the way I smelled in school after trapping. One Saturday night I went to

town for a show and during the movie the manager asked me to move to the

back of the theater. I guess someone had complained. It didn’t bother me

as long as I was netting several hundred dollars each winter.

Dad rented another farm, the Brown

Place, about 10 miles southeast, near the town of Onaka, during the

spring of 1924. We kept the lease on the Sam Wise Place also and Cully

stayed there for another year. I liked the new place as we were closer

to town where I could play baseball. I was old enough to go to dances

with the older kids and wanted to dance so badly, but was too bashful to

ask a girl. One of the older neighbors was dancing with a big fat Dutch

girl during a tag dance, so he backed up to me and let loose of her. She

thought I had tagged him, grabbed me and we WERE OFF! That broke the ice

and I probably didn’t miss a dance the rest of the night.

The great depression was getting

closer and times kept getting harder. We raised a lot of grain which I

would stack during harvest. I also cultivated the corn and could do any

kind of man’s work. We even did custom work for the neighbors to pick up

a few extra bucks. My folks weren’t too fond of the teacher at the

school near the Brown Place, so they sent me back to stay with Cully at

the Sam Wise Place to go to school near there. This school had a new

building and for the first time, indoor plumbing. Selmer Thorson, the

teacher, was an old bachelor with bad eyesight and poor hearing from

measles when he was younger. Some of the kids played tricks on him

because of his handicaps. When the teacher had a class reciting up

front, he would have his back to the room. One of the big boys would

wait until he had turned around and then pull out his can of tobacco and

cigarette papers. He would scratch the tobacco loose and the tin can

would creak and crack, but the teacher couldn’t hear him even when he

stood right in front of the boy’s desk. With the whole school watching,

he would finish rolling the cigarette, put it in his pocket, and ask to

leave the room. Mr. Thorson had a terrible temper, and we all shook with

fear for the boy, but he didn’t get caught. If he had, Mr. Thorson would

have beaten him unmercifully. Once he struck a boy with the stove poker

and put a big lump on his head. I did well in school that year, 8th

grade, as Mr. Thorson was a good teacher.

In the spring the folks had me come

back to the Onaka town school the last couple of weeks, to review the

year’s work. I took my 8th grade final exams at the county seat,

Faulkton. I got the highest grade in the whole Onaka district, which

made me very happy.

The summer of 1925 found things

about the same. . . a lot of hard work with very little profit. Dad was

indebted to the Tolstoy Bank and we could hardly make enough to pay the

interest on the loan. It was a losing game so we sold out and turned the

proceeds of the sale over to the bank. We decided never to have any more

debts! We had a few head of livestock that belonged to us kids. We made

our own harness and we boys took jobs to finance planting the crops.

Eunice and Hazel were both teaching and helping out at home. After

harvesting a fair crop though, we had so much rain that a lot of the

grain sprouted in the stacks and was worthless. We were able to eat from

the few cows and hogs we raised, but that was about all we had.

Dad was notified that the coal

dealer in Onaka had a carload of coal on the railroad track. He would

sell it at a reduced price if it could be removed within one day. The

team of mules Dad asked me to take were spoiled and would run away every

chance they got. I hitched them to the wagon with the high box, took the

scoop shovel, and went to town. The railroad car was on the side track

and I had to pull up between the two tracks to load. One was the main

track the train would be coming in on and the other track had the coal

cars on it. I thought I had time to get loaded and out of there before

the train came in. I had the lines tied to the railroad car where I

could get ahold of them in a hurry if the mules decided to make a quick

getaway. I just got the big load shoveled on when I heard the steam

engine whistle as it came around the bend. I knew it meant big trouble,

so grabbed the lines and stepped onto the load of coal. The mules reared

up on their hind legs as I tried to hold them into the side of the car.

They lunged forward and pulled out toward the main track and tried to

cross ahead of the train and get away from it. The load was too heavy

and when the front wheels hit the track, it stopped them. The steam

engine struck the mules and knocked them off the track, breaking the

wagon tongue. One of the mules was hurt and they were too scared to move

by that time I jumped off the wagon and started unhitching the team from

the broken tongue. One of the mules kicked me on top of the head as I

was down on my hands and knees. By that time the engineer had stopped

the train and came back to where I was. I was bleeding profusely. Several men

came real soon and helped me, one of them being the implement dealer who

sold wagons. He left and came back with a new wagon tongue and repaired

the wagon. I hitched up the mules and drove home, about 3 miles, with

the coal. When I got home, Dad took charge of the team and I went to the

house. Mother removed my blood soaked clothes and washed the wound. I

imagine some turpentine was used for disinfectant. There were no doctors

in the area at that time, so the wound wasn’t sutured and I still have a

large scar. The mules lived, but one was lame after that. They still had

enough life to cause many other runaways. I think it would have been to

our advantage if the train would have killed both of them. I would have

had one less scar and we would have been spared the later runaways.

That fall I started high school in

Onaka. It was held in a one room basement with one teacher for everyone.

There was very little choice of subjects and Latin was required. I hated

Latin and couldn’t see where I would ever need it, so I dropped out to

work on a dairy farm. The younger kids, Verna, Donald, Delbert and Inez

were all in grade school near the Brown Place.

The summer of 1926 was very dry and

crops were poor. We kept debt free by all the family helping at home

with income from outside jobs. That summer Onaka built a new two story

brick school house. I worked there most of the summer, pulling all the

materials up to the second floor with a hoist pulled by a horse. That

fall I tried going to high school again, but after a year of working it

was too much and I dropped out again. I have always felt this was a bad

decision.

The summer of 1926 was very dry and

crops were poor. We kept debt free by all the family helping at home

with income from outside jobs. That summer Onaka built a new two story

brick school house. I worked there most of the summer, pulling all the

materials up to the second floor with a hoist pulled by a horse. That

fall I tried going to high school again, but after a year of working it

was too much and I dropped out again. I have always felt this was a bad

decision.

The next three years were normal,

hard work for the entire family. Farm prices were low, but with everyone

working together, we were able to increase our livestock numbers. We had

some fun going to Saturday night dances, playing baseball and

basketball.

We had been dreaming of moving west

of the river and getting into ranching. The summer of 1929 Dad and I

took a trip to Dupree, South Dakota, and after several days of looking,

rented a ranch 9 miles south of Dupree, the Jake Maca Place. That fall

Dad, Mother, Verna, Donald, Delbert and Inez moved to the new place. The

folks shipped machinery and cattle by railroad. The farm equipment was

shipped in what was called an immigrant car. Donald and Delbert were

small and Dad had them hide under a wagon box in one of the cars to save

the price of the fares they would have been charged if they had been in

the coach. The boys said that every time the train went through a town,

some cars would be left off and others picked up, which caused a lot of

braking, It would throw them from one end of the box to the other each

time. When they arrived at Dupree they were happy and relieved, even

though slightly bruised.

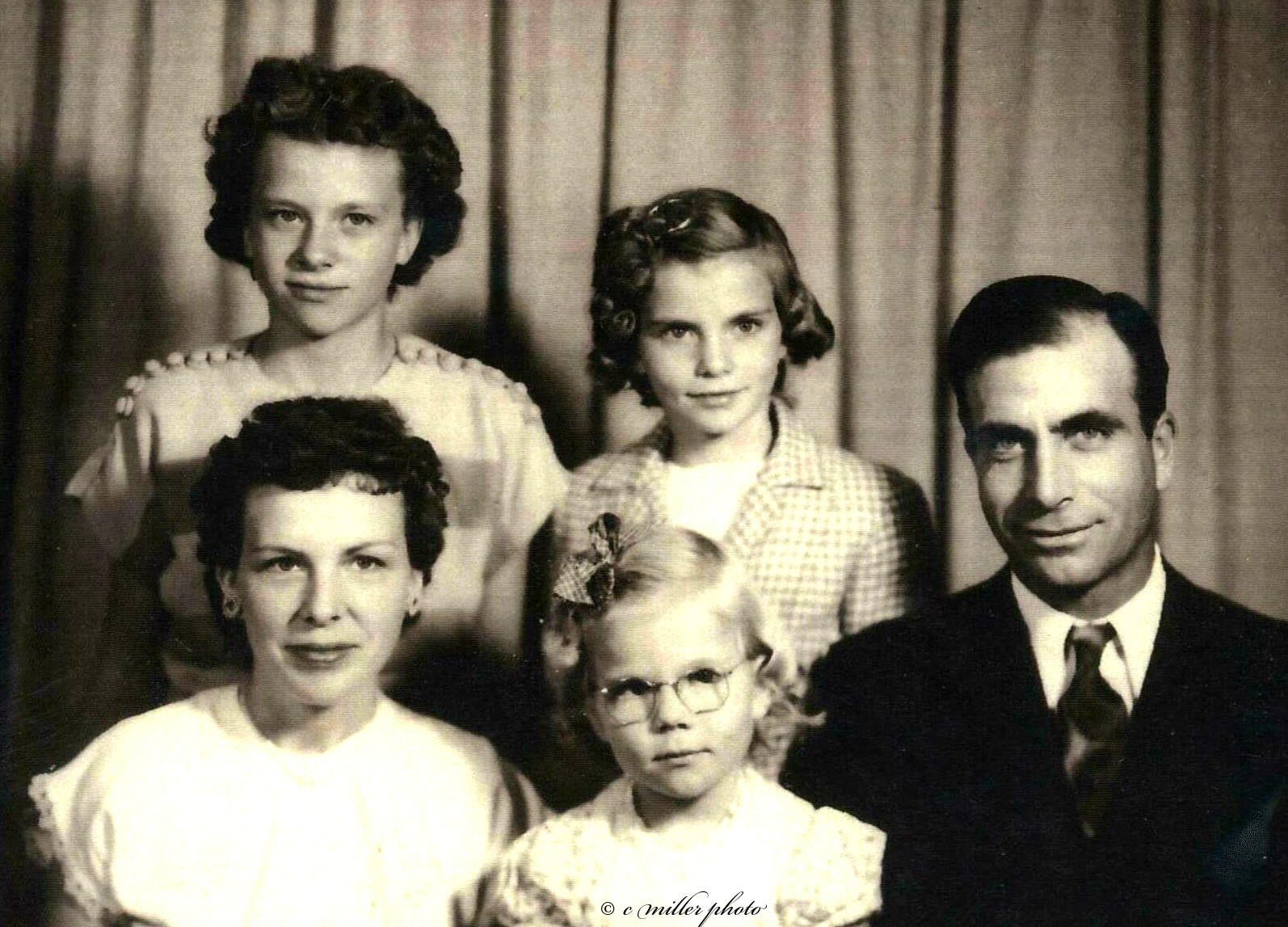

Cully in a covered wagon, and

Harlan Bitzer and I on horseback, trailed about 35 head of horses across

the country. When we got across the Missouri River I turned around and

went back to take care of my trap lines. Just after leaving them a

terrible storm moved in and got so bad Cully had to leave the covered

wagon and all the supplies at La Plante. They didn’t have an extra

saddle, so Cully mounted a bareback horse and they drove the herd 75

miles to Dupree. It took three days to get there and they could easily

have lost their lives.

Eunice and Hazel were teaching,

Fred was operating a farm and I was operating my trap line. When winter

set in hard the animals hibernated and trapping got poor. I packed up

and drove Fred’s old Model T Ford coupe to Dupree and joined the family.

Verna attended high school at Dupree and the three youngest went to the

Gage school, about 1½ miles southwest of our place. We gradually

increased our livestock and hogs. We did some farming, but prices were

too low, and as we moved into the depression of the 30’s they got even

worse. We milked 30 cows and sold cream, getting 12 cents a pound for

butterfat. Mother had a large flock of hens and sold eggs for 5 cents a

dozen. Cattle got so cheap you couldn’t sell them at any price so the

government started buying them at $20 a head for a good cow and $10 for

a good calf. To really finish us off, we were hit by the worst drought

the country had ever seen. This was followed by an infestation of

grasshoppers that cleaned up any vegetation that did grow. The ranchers

were forced to either ship their livestock to an area where there was

feed, or to sell them. Either way was a losing game. We had 50 young

pigs we tried to sell, but no one wanted them. Our cows all dried up

because there was no grass, so we couldn’t feed the pigs. Dad and I

couldn’t stand to see them starve, so we each took a hammer and killed

all but four that we could buy feed for until they were in shape to

butcher for meat. We sold the cows to the government and turned the

horses loose on the range, gambling on them to survive. Most of the

ranchers lost their land as they couldn’t pay the taxes. We were renting

the ranch but got way behind on the rent. We lived very cheaply, cutting

wood for fuel and even burning cow chips.

I had plenty of spare time, so I

started riding to Cherry Creek, the Sioux Indian Reservation, and got

acquainted with many good Indian people.

Our closest neighbors were the

Little Wounded family. James Little Wounded and his wife were quite

elderly when I knew them. Back in the days when the West was being

settled, the Indians and whites fought a battle known as The Battle of

Slim Buttes in northwestern South Dakota. After the battle, the band of

Indians, including James who was just a child, escaped to Canada.

Several years later when he had become a man, he came back to the U.S.

to claim his allotment of land, 160 acres bordering our land on the

southwest. He was a hard working, honest man. He had cattle and horses

and farmed on a small scale. We got along very well and we had a lot of

respect for the family. The old folks couldn’t speak English and I

couldn’t speak Indian, which caused a minor problem communication, I

think he got a little angry with me one time when I shot his big bull

with a shotgun, from a long distance of course so I wouldn’t kill it.

The bull came over to our place while we were milking our cows out in

the corral, and it chased us all into the house. Mr. Little Wounded must

have been just over the hill and heard the three shots because he came

up to me and said quite disgustedly, “You shoot bull!” and clapped his

hands three times. I got the message and tried to explain what had

happened, but I still don’t know if he understood. As time went on, we

became even better friends. When Mrs. Little Wounded died I hauled her

body to Cherry Creek in a two wheeled trailer behind my Chevy car, for

her funeral service.

James had a good sense of humor and

I think the language problem added to the humor. One day I was taking

him to town with my team of horses, so he could buy groceries. As we

rode down the road we tried to visit a little, but the language barrier

made it difficult. James’ oldest son Johnson, became a lay minister and is

retired now, living in Dupree. He is about 85 years old and a very good

friend. James’ oldest daughter married Felix Condon, who was my friend

and interpreter when I spent time on the reservation.

Cherry Creek was a small Indian

station which consisted of two general stores, post office, school,

resident government doctor, and Boss Farmer. The Boss Farmer was sort of

the manager, or advisor, who supervised the business deals and approved

purchases and sales of livestock. Cherry Creek is about 28 miles south

of our place, not very far with automobiles, but the trips then were

made with team and wagon or on a saddle horse.

I went to Cherry Creek for the

Missionary Convention, which was attended by Indians from all over the

U.S. and Canada. Cherry Creek expanded over night from a population of

about 100 people to several thousand. The area was covered with

thousands of teepees where they all camped. They had many Pow Wows which

are Indian Dances quite sacred in their native religion. They are quite

sports minded and had many contests between the local athletes and

visitors. I was very happy when they asked me to be on their local team.

My old friend, James Little Wounded, let me sleep at night in the box of

his wagon, which had a layer of hay on it, as I didn’t have any camping

facilities. The first morning I woke up to a terrible smell. They had

butchered in the night and were hanging the strips of fresh meat on the

wagon box to dry to so it would keep. The flies were thick all over the

meat, but I guess that was just part of the curing process.

The celebration lasted about a week

and was interesting to watch. During the celebration, an Indian lady

approached me, wanting to sell me a young, wild pinto mare. The horse

was located several miles up the creek so I bought her without seeing

her. My friend Felix said he would ride home with me and help pick up

the pinto on the way. He knew the country and where these horses were

located. This was important as the whole country was open range with a

lot of wild horses running loose. We found the band of pintos and roped

the one I had bought. After breaking her to lead, we started home on a

very hot day, across about 25 miles of wild country. We got to our home

after dark, tired and dirty, but one pinto richer.

In the early 1930’s we would ride

down on the reservation just to look at the hundreds of Indian horses.

In the late spring the prairie would be in bloom with all kinds of wild

flowers. The air was so pure, with no pollution of any kind, and smelled

as sweet as perfume. We would ride for miles without seeing anything

except wild animals and beautiful horses.

There was an old Indian named

Charging First, who had hundreds of beautiful spotted horses running

wild. One of his spotted horses strayed up into our country and ran with

a neighbor’s horses for about a year. Everyone coveted this horse.

Delbert and I decided to ride down to Charging First’s place and try to

deal for it. We knew about where he lived, but it was a long ride. We

saddled our horses really early and started south to find him. After

several hours of riding and asking questions of other Indians we saw

riding on the range, we found his place. His home consisted of a corral,

a log cabin and a squaw shade, located beside a timbered creek. In front

of his cabin was the usual barrel on a stone boat, used to haul their

water supply from the creek. There were a couple of beautiful spotted

saddle horses in the corral. We found Mr. Charging First sitting under

the shade as the day was very hot. He was well dressed in beaded

moccasins, a western hat and blue jeans, and wore his hair in long

braids. He greeted us with “How Cola”, which meant “hello friend”, and

shook our hands. After he had given us a good drink of water we sat down

with him in the shade. Our problem began as we tried to talk to him

about buying his horse. We tried sign language and everything else we

could think of, but by the expression on his face, it was obvious he

didn’t understand us., We couldn’t understand what he was saying either,

but we all knew we were talking about a horse. We would have given a lot

to have an Indian ride in who could interpret for us, but no such luck.

Delbert and I finally decided it was hopeless and we would come back

another day with an interpreter. We shook hands with the old gentleman

and rode towards home, arriving several hours later in the dark. We’d

had a wonderful experience. Later we learned that another neighbor had

beaten us to the horse deal!

My dad owned a beautiful palomino

horse that was broken to ride and drive. It was a really gentle horse.

“Irish Tommy” Condon, the stepfather of my friend and interpreter Felix,

was a very old man, almost blind. He wanted Dad’s horse. Felix said that

his stepfather had about 50 bills of sale for horses from as many

Indians, that he had accumulated over a period of years by making loans

to them. He would give all of the bills of sale to Dad for the palomino.

The understanding was that with Felix’s help. I would contact the

Indians and collect as many of the horses as possible. Most of these

bills of sale were several years old and we knew there would be a lot of

them we wouldn’t get. We learned that was the understatement of the

year!

Felix and I rode to Cherry Creek

and established our base at Irish Tommy Condon’s home, which was on the

Cheyenne River near the mouth of Cherry Creek. We expected to bring the

horses into our base as we gathered them. When the job was completed, we

would drive all of them to our place, 28 miles north.

Felix had a good laugh at me the

first place we spent the night. When we got ready for bed, our host

handed each of us a blanket and showed us our room, which was equipped

with an old bed and mattress. I waited for Felix to make up the bed. He

laughed at me and said, “It’s an old Indian custom to give each one a

blanket to roll up in separately.” I had a good Indian sleep.

We spent two weeks riding, most of

it in the rain. The rainy season was on, but at least it wasn’t cold. We

found that several of the Indians had died and I think the others felt

it was like the old saying, “Paying for a dead horse!” Felix did most of

the negotiating in their native tongue and I couldn’t understand what

was being said. After the first dozen contacts however, I noticed they

were using one word a lot. It sounded like “toska”. I asked Felix what

it meant, and he said it meant “later on”. “Sometimes,” he said, “they

mean next week, after awhile, next month, or just some other time.” I

found out later that was their word used to stall for time. In later

years I gave it my own interpretation, which was “NEVER”! After the big

roundup was completed, all we had was a lot of promises . . . it didn’t

take much of a corral to hold them. It was a great experience however,

and I learned a lot about Indians. They were the most generous people I

had ever met. We were always welcome to stay with them and they would

share anything they had. I am sure the reason we didn’t get any horses

is because after so many years had passed they didn’t have them. The

easiest way out for them was to promise to deliver “at a later date”. We

returned to our base slightly disappointed, but Irish Tommy was still

sure we would get some of the horses later on. Felix stayed with his

stepfather and I rode home the next day . . .alone and tired!

About two months later Felix

notified me that he had found two horses that we could get on the

palomino horse trade. They were located at the Frank Giles ranch on

Cherry Creek, about halfway between the northwest corner of the

reservation and the town of Cherry Creek. He said that he and Frank had

them in the corral one day and cut off their tails so we could identify

them if we found them running with other wild horses on the open range.

Delbert and I rode down to the Giles ranch and spent the night. Frank

was well educated and lived with his elderly mother. She had a large

steamer trunk full of beautiful Indian artifacts which she showed to us.

She had made many of them herself. The next morning we saddled up. Frank

was the fattest Indian I had ever seen. He rode a little brown horse.

His fat actually hung over the cantle of the saddle, but the little

horse could carry him well, and he could ride well.

We found the horses with the bobbed

tails and drove them, with some others, into the corral. We sorted them

so we only had the two we were to take left in the corral. We knew we

couldn’t drive two loose horses any distance, so we roped their front

feet and tied them down. We tied the head of one to the other’s tail.

That way, if one tried to run away, the other would hold back and they

wouldn’t run together. It took awhile for them to even walk together!

We got on our way, for the seven

hour trip home. We followed the creek to the mouth of Ash Creek, then

followed Ash Creek to about 12 miles from home. Here we had to angle off

to the northeast. When we left Ash Creek, we had to climb a high bluff

which was too steep to climb so we drove the horses ahead of us on a

path which climbed on a slant, following a path made by cattle. About

halfway up this high bluff the rear horse pulled back and both lost

their footing and rolled down the steep slope. The rope which held them

together caught on a tree stump and there we were with one horse hanging

by its head and the other by its tail. I remembered I had seen an axe

about a mile back, by a well, and told Delbert to stay there while I

went back to get it. Maybe we could free the horses before they died.

With all the pressure on the tree

stump it took just one blow from the axe to free the horses. They rolled

the rest of the way down the bank. The rest of the trip went well, as

the wild horses were tired. We got home late that night and decided that

if we added up the experiences, the trade wasn’t a total loss. We even

had two broncos to show for it.

In 1932 the Roosevelt

Administration went into office and started several programs to check

soil erosion as the fields were barren and would blow away, causing

terrible dust storms. The government financed the building of dams which

gave people work and assured a supply of water for livestock when it did

start to rain again. The Farm Security Administration made loans to

farmers so they could buy livestock to restock the range when conditions

got better. A price support program brought prices back to where people

could make a living, and gradually conditions got better for everyone.

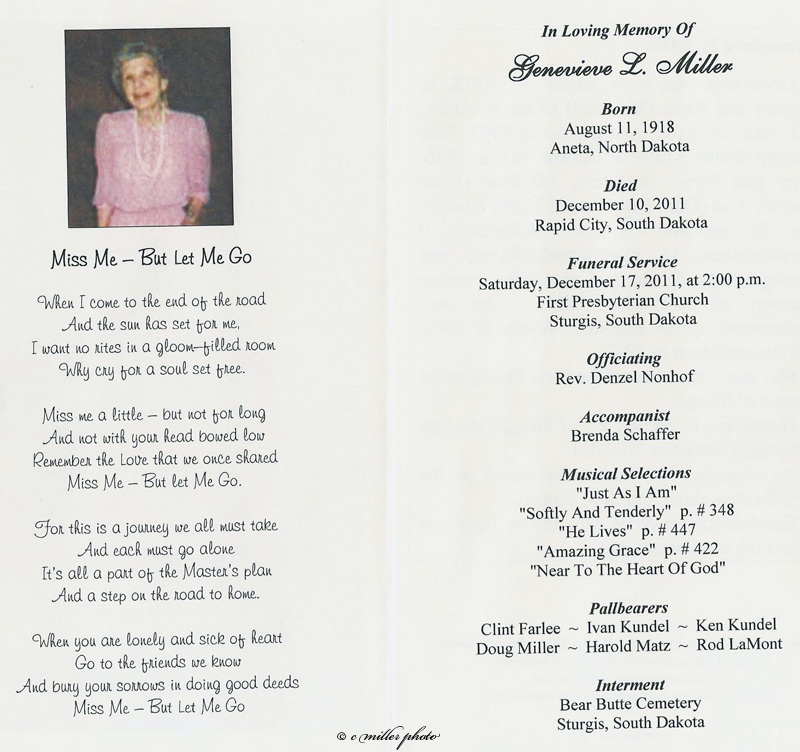

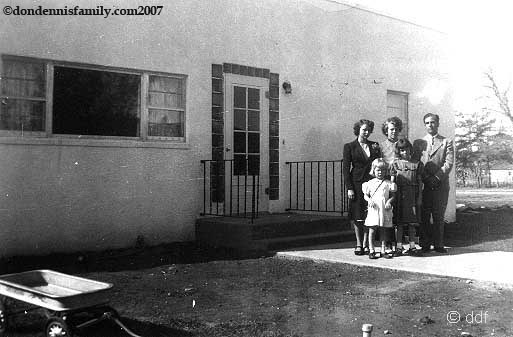

I courted Genevieve Olson mostly on

a saddle horse named Sox. Old Sox knew his stuff and was an expert at

shielding us from her grandparents when we said goodnight. Thank

goodness horses can’t talk! After a couple of years we decided to tie

the knot and we were married at Selby on March 28, 1936. We rented the Pevoy Place, 7 miles south of Dupree, which had been vacant a couple of

years. We made the old three room tar paper shack livable, though the

kitchen roof leaked like a sieve during the infrequent rains. The barn

had practically fallen down so I built a straw shed that got us by. We

took in some milk cows on shares and had a few cows and horses of our

own which gave us about $3.00 a week to live on from the cream we sold.

Nearly all the farmers were working on WPA and I got an appointment to

supervise the concrete work on construction of a dam. We worked very

hard on WPA. I would get up before daylight and milk 8-10 cows, do the

farm chores and then drive 10 miles to work. After a 10 hour workday, I

would drive home to the same chores and milk the cows again. It was a

cold winter with temperatures as cold as 20 below. I worked this WPA job

for two winters, until it was completed. In the meantime prices got

better. It began to rain and crops improved.

In 1938 my neighbors elected me to

represent them on the community committee, the Agriculture Adjustment

Act, better known as the Farm Program, or Triple A. In the fall of 1939

I was elected to serve on the Ziebach County Committee and was elected

each year for 10 years.

In 1941 the United States entered

World War II. We had rationing of tires, gas, sugar, machinery and many

other things. Hardships were encountered by families when husbands, sons

and fathers were drafted into the service. Donald and Delbert, and both

Verna and Inez’s husbands were sent overseas. Fred had his physical and

was about to be called. I felt it was wrong as he was 40 years old,

operating a 3,000 acre farm and keeping Dad and Mother. I talked to the

local draft board and got nowhere, so contacted General Hershey, who was

the administrator of Selective Service in Washington, D.C., and

requested an investigation. Immediately his draft status was changed and

he stayed on the farm where he should have been.

Delbert was a bombardier on a B29

in the Pacific war theater. Their plane was shot down by anti-aircraft

fire over Tokyo, Japan. Delbert was captured and tortured

severely by

the Japanese. The most painful task I have ever had was the day I had to

bring Mother and Dad the news that their youngest son was missing in

action. He never fully regained his health, but did return home. He was

promoted to 1st Lt., and was one of the most decorated war heroes in our

state. The Indians are extremely patriotic. They invited Delbert to

Cherry Creek where he was taken into their tribe. They held the ceremony

in a community hall with a very large crowd attending. Several patriotic

speeches were made and the tribal leaders christened him “Flying Eagle”.

A cash gift was presented to him and a big feed (as they called it) was

enjoyed by all. I went with Delbert and we all participated in the Pow

Wow, or sacred Indian dance.

severely by

the Japanese. The most painful task I have ever had was the day I had to

bring Mother and Dad the news that their youngest son was missing in

action. He never fully regained his health, but did return home. He was

promoted to 1st Lt., and was one of the most decorated war heroes in our

state. The Indians are extremely patriotic. They invited Delbert to

Cherry Creek where he was taken into their tribe. They held the ceremony

in a community hall with a very large crowd attending. Several patriotic

speeches were made and the tribal leaders christened him “Flying Eagle”.

A cash gift was presented to him and a big feed (as they called it) was

enjoyed by all. I went with Delbert and we all participated in the Pow

Wow, or sacred Indian dance.

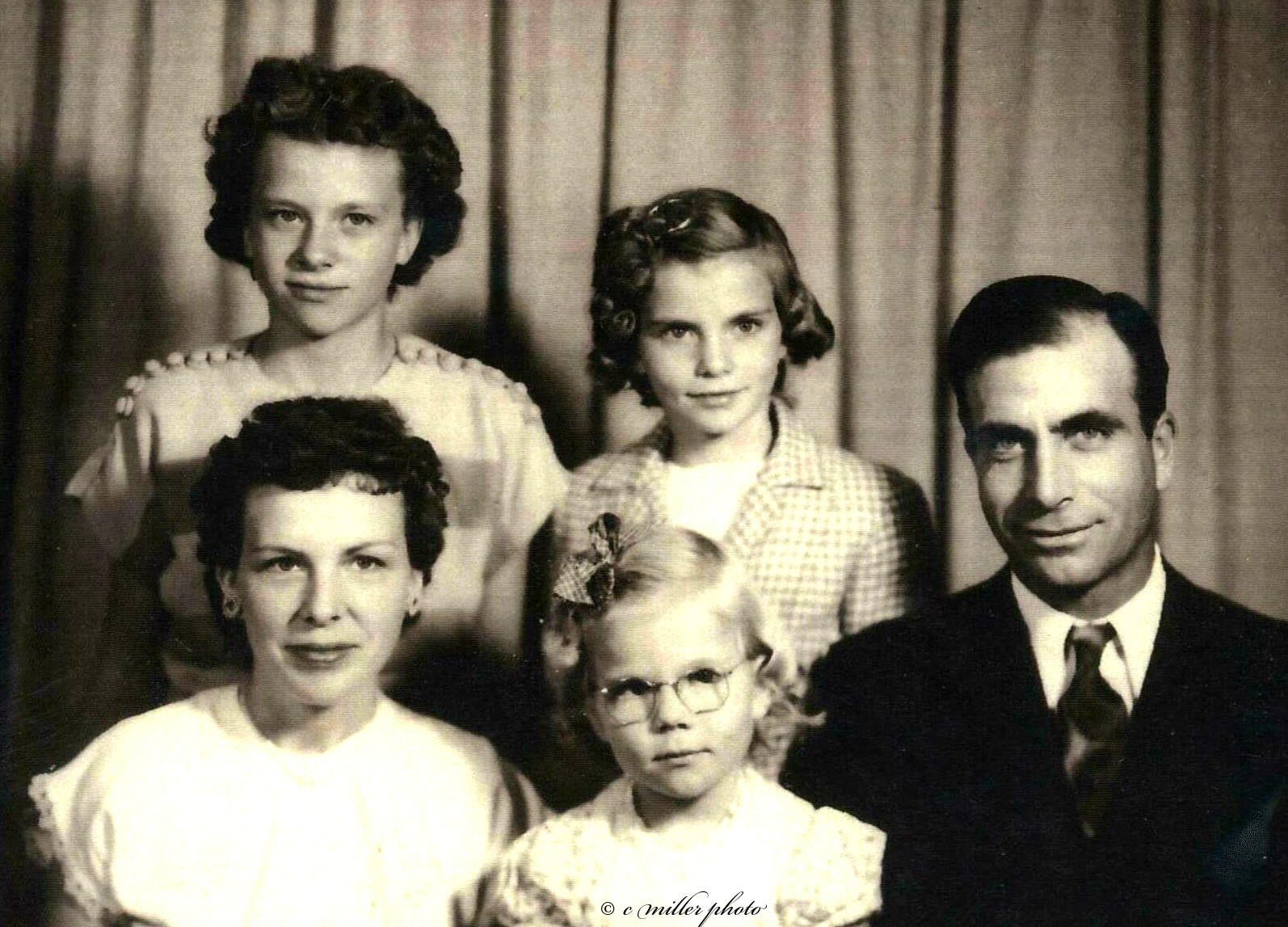

Materials of all kind were in short

supply during the war and for some time after war’s end. We built a

house at that time and I almost wore out a car running all over the

country looking for materials. Our family had grown with the addition of

three girls, Marlene, Ann, and Karen. We were living in a house we had

bought from a family who had left the country during the great

depression. We tore it down, along with the black

shack and used the

materials to build a new house beside the dam. A lot of trees grew up

along the shoreline, which made a nice yard for us. The girls could go

fishing any time they wanted and many times I would come in from the

field and have a fresh fish dinner they had caught. We had an old Chevy

coupe Marlene learned to drive when she was only 7. She used to bring me

lunch and things I needed when I was in the field. She had a few

mishaps, but none too serious. Ann liked to ride horseback and fell off

Dad’s old Rosie several times, but usually managed to get back on. Karen

was always the cat lover and had a beautiful yellow cat named Fluffy.

Fluffy was always having kittens. One day I heard Karen tell a little

friend that her cat’s name was Fluffy and she’d had a MILLION kittens!

shack and used the

materials to build a new house beside the dam. A lot of trees grew up

along the shoreline, which made a nice yard for us. The girls could go

fishing any time they wanted and many times I would come in from the

field and have a fresh fish dinner they had caught. We had an old Chevy

coupe Marlene learned to drive when she was only 7. She used to bring me

lunch and things I needed when I was in the field. She had a few

mishaps, but none too serious. Ann liked to ride horseback and fell off

Dad’s old Rosie several times, but usually managed to get back on. Karen

was always the cat lover and had a beautiful yellow cat named Fluffy.

Fluffy was always having kittens. One day I heard Karen tell a little

friend that her cat’s name was Fluffy and she’d had a MILLION kittens!

Having no electricity or bathroom,

the little house at the end of the path was a real necessity. Ours had a

slight cave-in on the north side and the cold wind blew in just in all

the wrong places. I decided to remedy this by dumping the ashes from the

furnace along that edge. This worked very well. One night I was in a

hurry as we were going to a movie in town, something we rarely did. I

hurried to get all the chores done early so we could be there in time.

As we drove over the top of the last hill on our way home, I said to

Gen, “Look at the huge golden moon tonight.” She replied, “That isn’t

the moon – our outhouse is on fire!” Sure enough, when we got to the

yard, only a smoldering pile of red coals greeted us where the little

house used to sit. Fred had bought an old schoolhouse, complete with two

outhouses, and he agreed to sell one to us. Now we were really in style,

for this little house had three holes instead of the usual two. From

then on we bragged we were a “three-holer family”.

In 1949 the South Dakota State AAA

Committee notified me that there was a civil service opening for an

administrative assistant in the state office at Huron. After talking it

over, we decided I should try for it, as we wanted to get closer to good

schools for the girls. I received the appointment and was assigned a

territory of 12 counties, most of them located west of the Missouri

River. My job was to coordinate work between the state and county

offices, and to assist counties in soil and water conservation, price

supports and crop insurance. We rented the Dupree ranch to Donald and

Florence, but lived in half of the house until we could get a place to

live in Spearfish. In March of 1950, we bought a house and hired a

Deadwood moving company to come to Dupree to move our possessions. Just

before we were to move, a warm spell began which thawed the snow and

took most of the frost out of the ground. The water rose in the creeks.

The mud was so bad we had to park the moving truck three miles away on

Cherry Creek Highway and haul everything to it with tractors and

trailers. Several neighbors helped us. When we finally got everything

loaded and the truck on its way, we packed some bedding and a small

breadbox of food in the car and the family began the journey. The wind

switched to the north, bringing in a blinding snowstorm. Darkness

overtook us, and when we drove through Belle Fourche we could hardly see

the streetlights in the storm and darkness.

It was late at night when we

arrived at our Spearfish house and the moving van was not there. We

spread the bedding on the floor and got a badly needed, short nights

rest. There was no food in the house and we hated to go downtown wearing

the clothes we had worn while loading the moving van in the mud, but I

finally decided to forget pride and get everyone something to eat. That

afternoon the van came and we could clean up.

The next morning I had to go back

on the road for my job so Gen was left with the big responsibility of

getting the family settled and the girls into school. When I came home

the next weekend the house was cozy, the kids had made new friends in

school, and everything was great.

After living in the old house a few

months however, we put it up for sale. While I was out on the road, Gen

sold it and we had to find a place to stay. The new owners agreed to

rent one large bedroom to store our things until we could build a new

building. Since it

was summer, the family went to Dupree and stayed in a

little shack in Delbert and Eva’s yard, until school started. Then we

went back to Spearfish and rented a one room cabin as the contractor was

behind schedule. Finally the great day arrived that we could move in! I

was assigned some new counties and loved my job. It was made easier with

Gen as my secretary. She had taken journalism in school and could write

news releases and correspondence that really opened the eyes of the

people in the state office.

was summer, the family went to Dupree and stayed in a

little shack in Delbert and Eva’s yard, until school started. Then we

went back to Spearfish and rented a one room cabin as the contractor was

behind schedule. Finally the great day arrived that we could move in! I

was assigned some new counties and loved my job. It was made easier with

Gen as my secretary. She had taken journalism in school and could write

news releases and correspondence that really opened the eyes of the

people in the state office.

With the family in the new home and

everyone happy in school, we thought we were off to a good start – until

winter arrived. We discovered that the block house, because it wasn’t

furred out and insulated, built up moisture on the inside. In extremely

cold weather the moisture froze into a sheet of ice on the walls that

were furthest from our inadequate heating system. After suffering

through the winter, we decided to sell. It was easy to sell because it

was a beautiful place with the creek, plus the fruit and shade trees we

had planted.

Gen hadn’t been feeling well. The

doctor said she’d had a light heart attack and the high altitude in

Spearfish wasn’t good for her. I had been assigned extra counties in the

central and southern Black Hills, so we decided Sturgis would be an

ideal headquarters. The altitude was lower and we would be closer to the

ranch at Dupree.

We rented a house in Sturgis, found

a contractor to build a new house which was competed without too many

problems, and again rejoiced when we were able to move in.

The national election brought a

change of administration in Washington, and even though I had the best

civil service rating of all the fieldmen in the state, I was notified

that I no longer had the job. The agency was putting office managers in

each county office. I applied in Meade County and got the appointment.

Things worked out really well as I could stay home with the family at

about the same salary as when I traveled all the time. Gen found work

also at the office of an optometrist.

I won several awards while managing

the Meade County office from September 1952 until 1960. The one I

treasure most is the award for the most outstanding office in the

fieldman’s area of 12 counties, and second most outstanding office in

the state. A large share of the credit was due to my four good

secretaries, and I told them so.

After a few years of living in

Sturgis, I started itching for some land again. We sold our house in

1956 and bought 60 acres of unimproved land 5 miles east of town. We

hired a contractor to build a house, drilled a 915 foot flowing well and

planted a lawn, big gardens, strawberries, and fruit and shade trees.

With plenty of water, everything did so well that today we are almost

hidden from the road by the big trees. We harvest apples for our own use

and to give to relatives and friends. There is a small creek running

behind the house, with a lot of trees along the creek. We have lived

here since July of 1957.

During the first few years on this

place, we brought out some horses from the Dupree ranch. I traded for a

couple of milk cows, and we were once again ranchers . . . on a small

scale. After a few months we sold the cows.

The national administration changed

again in 1960 when Jack Kennedy was elected president. Several changes

were made and I was given back my fieldman position. I was really happy

to be back, and my counties all gave me a good welcome. The agency

started training programs. I was given short courses in psychology and

public relations at South Dakota State College and Idaho State

University.

With only Fred living at our ranch

at Dupree, we drove there nearly every weekend and kept the place going.

On January 1, 1969, the Hills

received an enormous amount of snow and Dupree had the most snow it had

ever received. Gen went to Dupree to feed the cattle and cook for Fred.

When I got back to Sturgis from my traveling one Friday night, I got

word that Fred had gone to Gettysburg for a truckload of corn for his

cattle. While he was snowbound there, Dupree had a total power out. I

almost panicked with Gen at the ranch with no heat – all the roads

were

blocked from the ranch to town. I went to a dealer in Sturgis at

sundown, and he showed me snowmobiles. I had to have him show me how to

run the one I bought, then loaded it on the pickup and headed for

Dupree. I got there about 8:30 that evening, unloaded the snowmobile and

left the pickup in Buck’s [Delbert’s] yard. The night was pitch black

when I headed for the ranch. The snow completely obliterated the road.

Drifts were 10-12 feet deep. I must have tipped over a dozen times, but

would turn it over and start out again. Finally I made it to the ranch

and learned Gen had figured out how to run the furnace without

electricity. It was supposed to require a thermostat to operate. The

wind was so strong that it created a draft; Gen had cut up old fence

posts to add to the coal. The house was warm and homey. She had

everything under control, but was so glad to see a human being and get

some very welcome mail. The cattle looked good after Gen’s care. I spent

the weekend and fed cattle for her, but then had to get back on the job.

I piloted the snowmobile the 7½ miles back to Dupree and left it in

Buck’s yard.

In the fall of 1969 I retired from

my job with the U.S. Agriculture Department and we moved back to the

Dupree ranch full time for 4 years. We rented our Sturgis home and moved all of

our possessions to the ranch. I liked it there, but Gen wasn’t too fond

of it. She was tired of being snowbound in the winter and mud-bound half

the summer. Fred had moved into a mobile home in Dupree.

I sold the cattle in the spring of

1973, and in May we began to move back to our Sturgis home. Since

retirement I have begun rock collecting and have some very nice

specimens. Gen collects dishes. We are both active in church and

stay busy taking care of the yard, garden, and doing all the things it

takes to keep a home together. Our biggest blessing is our family.

I lost both of my parents and three

brothers between 1956 and 1984. I have lived during both Word Wars, the

Korean War and the Vietnam conflict. I have seen 13 Presidents come and

go. I have lived 74 years, but I don’t feel OLD . . . just not as young

as when “it all began”.